吃驚 BIKKURI

2010年10月23日(土)~11月21日(日)

山本 聖子

YAMAMOTO Seiko

撮影:山本糾

自立した空白

日沼 禎子

夜の最終便で大阪空港へ。ドスン、と到着し、東へ向かう高速バスに乗り継ぐ。自動車やタイヤの広告塔、ガソリンスタンド、スーパーマーケット、白やオレンジの街路灯たちを車窓に眺めては、追い越していく。高速道路からの風景など、何処も同じようなもの。けれども何故だか通る度に気になって、視線を奪われる場所。丘陵地を占拠し、まるで光の要塞のように闇に浮かぶもの。その正体は、万博公園に隣接する広大な住宅街に連なる中高層住宅群。日中、周囲の緑とコンクリートがコントラストを見せる風景は、夜は光と闇との、その際立つ人工美へと姿を変える。縦横に規則正しく区切られた階層、同じサイズの窓。1Kや2DKや、4LDKに規格された空間の連なり。無機質で無個性の、ミニマルな環境。しかし、それはあくまでも外側からの視点にすぎず、そのひとつひとつの窓からの光は、その光の数の分だけの、人々の暮らしがあることを証明してみせている。ある人はソファで静かに本を読み、ある人はヘッドホンから聞こえる大音量の音楽を聴き、ある人は温かいスープを分け合っているかもしれない。バスの心地良い振動に身を任せながら、そうしたそれぞれの営みに思いを巡らせていると、やがていつものように心地よい眠りが降りてくる。山本聖子が育ち、現在も居を構える、ここ、千里ニュータウンは、戦後日本初の大規模ニュータウンとして開発され、1962年にまちびらき、その8年後の70年には「人間の進歩と調和」をテーマに掲げた大阪万博開催のため、更なる土地開発が進められた、いわば、戦後日本の高度成長を最も象徴する場のひとつである。81年生まれの山本にとって、時は日米安保闘争やベトナム戦争が終息し、ベルリンの壁崩壊、そして冷静の終結へと世界がグローバル社会に向けて舵を切るその途上にあった。そうした内外の激動の気配を無意識の中に覚えながら、毎日、この街の空を見上げてきたのだろうと思う。

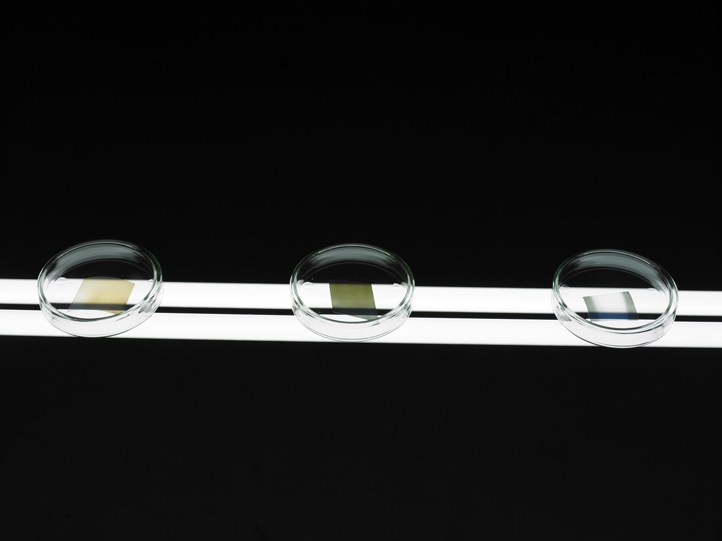

ACACにおいて山本は、≪independent empty(自立した空白)≫、≪the empty shadow(空白な影)≫、≪peeled light(剥けた光)≫の3点を制作した。ギャラリーのエントランス近くに据えられたこれらの作品は、空間を共有する1つのインスタレーションとして見ることができるが、しかし、それらは、個々に独立した彫刻作品である。それぞれのタイトルにある「空白」「自立」「剥ぐ」という言葉は、極めて彫刻的な概念として選ばれている。前者2点は、近年山本が取り組んでいる手法を新たに展開させたもので、新聞の折り込みチラシなどで良く目にする広告の間取り図を切り抜き、ラミネート加工によって素材を強化し繋ぎ合わせる手法で作られ、形もスケールも自在に変化させることができる。≪independent empty≫は、縦560cmx横520cmに間取り図を繋ぎ合わせ、網上の壁がコンクリートの床に垂直に立ちあがるかのように天井から吊されている。脆弱な線によって繋がれた壁は重量を感じさせず、プラスティックの表面が照明の反射によって微細に輝き、向う側の景色を透かして見せ、また、モノクロ1色の表面に対し、裏面はさまざまな印刷色に彩られている。≪the empty shadow≫は、同じく間取り図を直線状に繋ぎ合わせたもので、地上から約4mほどの高さから吊るされており、ギャラリーの壁に微かにその影が映し出されている。私たちは天を仰ぐ格好で入口からギャラリー奥に向かって伸びる線を目で追うが、終わりなくどこまでも伸びゆくような可動性を感じ取ることもできる。≪peeled light≫は、天井から吊るされた2本の細い蛍光管の上に、8個のシャーレが載せられている。シャーレの中には、3~4cm角程の台形状に切り取られた色の異なるフィルムが1枚ずつ入れられている。このフィルムは、山本が夜の集合住宅の窓を撮影した写真を透明シートに転写し、切り取ったものである。それぞれの制作にかかる膨大な仕事量と時間の長さを想像するに易いだろう。しかし、いずれの作品も、手仕事と思考の痕跡は削ぎ落とされ、個性というものが一切剥ぎ取られている。私たちはそこに佇むとき、その柔らかな光と影のコントラストが作り出す美しさに身を沈めることができるが、ここにある3つの作品が何を意図し伝えようとするかを感じ、受け止めることはできない。やがて作品に近付いて仔細に観察し、広告の間取り図や、集合住宅の窓であることに気付いた途端、私たちの想像が宇宙的に広がっていくことを感じるだろう。空白の中にある無限。あるいは、見えないものを見ようとする人間の欲望。山本が彫刻に求める強度とは、物質としての重さや質感を超えたところにあるもの。そこに在り、人々がその対象へ向き合うための自由を約束し、受け止めること。それは「器」であり、今は空っぽである間取り図は、過去の誰かが、そして未来の誰かが暮らす場所としての「器」を象徴する。その集合体による構成は、解体と再生を繰り返し続ける街の姿にも重ねられ、現代の都市へと差し出されたモニュメントのようでもある。

さて、何かを受け止めるものとしての「器」への探究は、「器」そのものを用いてきた過去の経験から連綿と繋がっている。2006年に発表した≪phenomenon―混Chaos≫(1)(fig.1)、≪Untitled≫(2)(fig.2)では、素焼きをせず乾燥させただけの土の器が、水の浸食によって破壊されるプロセスを表した。また、同年発表の≪ZERO≫(3)(fig.3)では、壊れた器をステンレスメッシュに置き換え、元の器の形に形成してみせた。ある種、パフォーマティブな作品ではあるが、ここでも限りなくアーティスト自身の気配は消し去られている。そこに立ち、存在するものとしての彫刻(物)が語りかけるのではなく、対峙する人々に物語を委ねる。「器」そのものだけではなく、内包され、扱うもの所在、振る舞いへの興味。山本は、均一化によって失われる身体性、曖昧になる個々の存在を「とにかく、舐めて、触れて、確認したいのだ。」と言っている。

かつてリチャード・セラが1981年にニューヨークの連邦政府ビル前に制作した≪傾いた孤(Titled arc)≫は、国家事業の公共性をめぐる問題であると当時に、都市空間における建築、美術の関係性に対し大きな問題を投げかけた。巨大な鉄を都市の中心に屹立させた者と、都市の現在を柔らかなプラスティックに包み顕在化させようとする者。30年という月日を経て、私たちは、実体不明な社会の中で、不確かに漂い続けるのだろうか。山本がそうして作り出す「器」は、すくいあげ、こぼれ、残る、固体であり液体のジェル状の危うさと、その危うさゆえの美をたずさえて、ここに自立している。

-----------------------------------

(1) 一方の器には天井から一滴ずつ水滴が落ち、穴が開く。次第に器はバランスを失い変形する。もう一方の器には、作者が直接水を注ぐ。急激な土の膨張で、器は爆発的に破壊する。

(2) 100個の焼かれていない器を鉄板の上に置き、水を注ぎ込む。次第に器は割れ、水が流れ出し、鉄板の上に鮮やかな黄色(錆色)の痕跡を作り出す。

(3) 紙の上に置いた土の器に水を入れ、器が壊れる。その破片を鉛筆でトレースし、その線をもとに型紙をおこしたものをステンレスメッシュに置き換える。

《peeled light》

《the empty shadow》

撮影:山本糾

fig.1 《phenomenon-混 chaos》土、水、紙、アルミ、270x270cm(紙)、直径70xh50cm(器)、2006年。

fig.2 《Untitled》土、水、鉄、450x180x10cm、2006年。

fig.3 《ZERO》ステンレスメッシュ、紙に鉛筆、土、綿糸、アルミ板、270x450x300cm、2006年。

吃驚 BIKKURI

October 23 -- November 21, 2010.

YAMAMOTO Seiko

山本 聖子

photo: YAMAMOTO Tadasu

Independent Empty

HINUMA Teiko

Boarding the last plane to Osaka at night, I got there and changed to an eastbound express bus. Outside the window, I saw scenes flying past---advertising towers of motorcars and tires, service stations, supermarkets, and streetlights shining white and orange. The view from the highway looks alike everywhere, but I can’t help looking out the window whenever I go on a highway. I don’t know why. The scenery occupying a hilly area like a fortress shining in the dark is actually a group of high-and-medium-rise buildings in a vast residential area adjoining to the Expo Park. It shows a good contrast between the surrounding greenery of trees and concrete buildings by day, and by night it turns into remarkable artificial beauty of light and darkness. There are regular crisscross lines of floor levels, identical windows of the same size, and a series of living space standardized as 1K, 2DK and 4LDK. They make an inorganic and impersonal minimal environment. However, this is only a viewpoint from the outside. The light from each window demonstrates that there is the same number of households as that of lights. There may be someone reading a book lying on a couch, or listening to loud music wearing headphones, or sharing hot soup with family. While feeling vibrations of the bus and thinking about how they were living, I drifted into a pleasant sleep as usual. Senri New Town, where YAMAMOTO Seiko was raised and currently lives, has developed as the first Japanese large-scale new town after the war. It started as a town in 1962, and after eight years, further development was planned to host World Exposition in Japan whose theme was “Progress and Harmony for Mankind.” It is one of the most symbolic sites representing rapid economic growth of post-war Japan. Yamamoto was born in 1981 in the times when the movement opposing the Japan-US Security Treaty and Vietnam War had ended, the Berlin Wall collapsed, and the world was shifting the helm to the termination of the Cold War, and the society has been in the process of globalization. Yamamoto probably looked up at the sky over this town everyday, vaguely feeling the signs of turbulent world at home and abroad, which she was not wholly aware of.

At ACAC, Yamamoto produced three pieces, “independent empty,” “the empty shadow” and “peeled light.” These works installed near the entrance of the gallery are possibly regarded as a single installation sharing the space, but each of them is considered an independent piece of sculpture. Three words contained in their titles, “empty,” “independent” and “peeled,” were chosen as having sculptural concepts. In the first two works, Yamamoto has developed a new method that she has been tackling recently. She cuts floor plans out of advertising leaflets you often see in newspapers, and after laminating them for reinforcement, she joins them together, so shapes and scales can be changed easily. “Independent empty,” in which floor plans are connected so as to form a square of 5 meters, is suspended from the ceiling just like a netlike wall standing at right angles to the concrete floor. The wall made of delicate connecting lines does not appear to be hefty, and the plastic surface shines delicately by the reflected light of a chandelier, through which the scenery of the other side is visible. As opposed to the monochrome surface, the other side is colorful with different colors of printing ink. “The empty shadow” is also a piece in which floor plans are connected linearly. It is suspended from a height of about 4 meters above ground, and its shadow is slightly shown on the wall of the gallery. Following a line extending from the entrance to the interior of the gallery with your eyes as if you were in a pose of looking up at the sky, you might feel the mobility of the line growing endlessly. In “peeled light,” eight Petri dishes are placed on two thin fluorescent tubes hanging from the ceiling. Each dish contains a cutout film in a three- to four-centimeter trapezoid shape whose color is different from one another. Yamamoto made these films by copying photos of collective housing she photographed at night onto transparent sheets and cutting them out. It can be readily imagined that this task took her a lot of time and workload. Each piece of work shows, however, no sign of handwork and thinking process as well as individuality. Standing for a while, I can immerse myself in the beauty created by the contrast of light and shadow, but it is difficult to understand and respond to what all these three works intend to convey to us. I approached them to watch more carefully, and the moment I noticed that they were floor plans for advertisement and windows of apartment houses, I felt my imagination stretching globally. Such things as eternity in emptiness or our desire to watch what is invisible are the strength that Yamamoto expects in sculpture and what comes beyond the weight and texture of the material. That is what exists there and promises us freedom to deal with the object. Containers or vessels fulfill such quality, and floor plans that are now empty symbolize “container” in which some people lived in the past and some people will live in the future. The make-up of an aggregate is associated with an aspect of a town in which dismantling and rebuilding are repeated. It is similar to a monument presented to us to think about a present-day city.

The pursuit of “container” as an object that holds something has continued unbroken for long since the experience of using “container” itself in the past. In “phenomenon-chaos” in 2006(1) (fig.1) and “Untitled”(2) (fig.2), she depicted the process of how earthenware, which is dried without bisque firing, is destroyed by water erosion. Also in “ZERO”(3) (fig.3) produced in the same year, she replaced broken containers with stainless steel mesh to restore their original forms. The work is somehow performance-related, but the presence of the artist is entirely eliminated here again. Its story is told not by a piece of sculpture (an object) existing there but is left for the viewer who confronts it. Her concern is not “container” itself but her interest lies in what is latent, how it exists and how it is appreciated. According to Yamamoto, she wants “anyhow to lick, touch and confirm” individual existence that is becoming vague by losing physical presence due to standardization.

Richard SERRA’s work “Tilted Arc” made in front of the Federal Government Building in New York in 1981 caused a sensation regarding the issue over the public nature of national projects and the relations of architecture and arts in city space. One artist makes a huge iron sheet soar high above the center of the city, while another tries to reveal the present state of the city wrapping it in soft sheets of plastic. After the lapse of 30 years, are we still floating precariously in unidentifiable society? “Container” that Yamamoto thus creates has jelly-like delicacy; you scoop it but it drops off, and it remains to be neither solid nor liquid. Here the container exists independently carrying such delicate beauty.

-----------------------------------

(1) Water drips from the ceiling into one container and makes a hole in it. The container gradually loses its balance and is deformed. The other container is filled with water directly by the artist. Sudden expansion of clay explosively breaks it.

(2) One hundred unbaked containers are placed on an iron sheet, and water is poured into each of them. They gradually break and water flows out. On the iron sheet appear bright yellow (rusty) traces of water.

(3) Water is poured into a clay container on a sheet of paper, and it breaks. The broken pieces are traced with a pencil. A paper pattern based on that outline is cut and remade with stainless steel mesh.

photo: YAMAMOTO Tadasu

fig.1 phenomenon chaos, clay, water, paper, aluminum etc, 270x270cm(paper)、70xh50cm(vessel), 2006年。

fig.2 Untitled, clay, water, iron, 450x180x10cm,2006年。

fig.3 ZERO, stainless, pencil on paper, clay, string, aluminum, 270x450x300cm, 2006年。