吃驚 BIKKURI

2010年10月23日(土)~11月21日(日)

狩野 哲郎

KANO Tetsuro

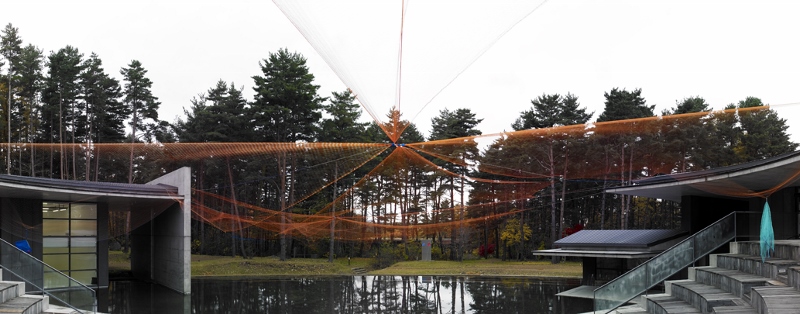

《自然の設計/Natureplan》インスタレーション 撮影:山本糾

予兆の場の創造

近藤 由紀

口を大きく開いて餌をねだる雛たちに絶えず餌を運ぶ親鳥は、必ずしも自らが生んだ子どもへの愛情から彼らを育てているわけではない。親鳥はある行動の結果現れた目の前で大きく口を開く、眼の大きな生物を「子孫」とみなし、それを育てるように生まれついている。だから時に卵がすり替えられ、自分より大きな異種の子どもがそこで口を開いていても、わが子と同様に何事もなかったかのように育て上げるのである。

狩野哲郎の作品タイトル≪自然の設計/Naturplan≫は、動物学者ユクスキュルの著作から引用したものであるという。あらゆる生き物は、それぞれの知覚をもっていて、その知覚によって都合のいいように情報を変換して世界を解釈し、それに基づいて行動している。例えば人間生活にとっては障害物である道を塞いだ倒木をモグラは快適な住処とみなし、アリはそれに食欲をそそられる。あらゆる生き物がそのような形、機能、器官を備えることとなったのは「自然の設計」によるものであり、それぞれの環世界で生きるためにあらゆる生き物はこの自然の設計の支配を受けて世界を知覚し、それに組み込まれた行動をしている(1)。

狩野の作品は動植物が取り入れられることでも知られている。2004年の最初期の作品≪発芽―雑草/Weeds≫(fig.1)から植物が使用され、作品の中にその生育の過程が取り込まれている。2009年の≪それぞれの庭/Respective garden≫(fig.2)からは、そこにチャボが加わり、作品をより有機的に変化させる偶然性が増していった。≪自然の設計≫は、これ以降のシリーズ作品につけられているタイトルでもある(fig.3)。狩野はこの鳥や植物を作品に取り入れようとしたきっかけについて、空間の機能や価値や意味について学んでいたときに、それらは全て基本的に人間のためであるという事実、そして例えばコンクリートの「破損」である裂け目は人間の環境にとってのマイナスの要因であるが、植物にとって「生育の場」になるという事実に気付いたことを挙げている(2)。こうしてこれらは狩野の作品において既存の空間の異なる意味や価値を見出すための媒介として導入された。

狩野のインスタレーションにおいては、ネットやポールといったホームセンターなどで気軽に手に入るような素材が集められ、場に構成されていく。色彩豊かなそれらが空間に広がる様子は、あたかも三次元の空間に施されたドローイングのようでもある。この中にその動植物が放たれる。作品の中に置かれたリンゴは会期中に腐り、落下し、粘性の高い汁を滴らせ、展示物としては「相応しくない」姿をさらす。放たれた鳥は、当初は美しく「展示」されたこうしたリンゴや種子を餌としてついばみ、その綺麗な円錐状の山を崩し、その食した結果としての排泄物を散らす。展示物としての植物や種子は、そんなことはお構いなしにある条件が来たら発芽し、そしてまたその鳥についばまれたりする。そして時々あまりに散乱したかのように見えたその場は、作家の手によって掃除され、形を整えられ、インスタレーションとして保たれる。ある完成形を持っていたかのように見えたインスタレーションはこうして会期中にそれぞれの主体の世界の中で、互いに関わりあいながら、一方で干渉しあわないまま共存することとなる。

ところで狩野はこうした偶然の展開を生む作品の中の動植物を「完全なる他者」とみなし、「コントロールできないもの」としているが(3)、おそらくそれは単純に不測の事態を生むもの=作品の状態をコントロール不可能にするものとみなしているわけはないだろう。それがどのような方法であれ自然の物事に対して物理的/精神的な働きかけを行い、なんらかの「コントロール」を施し、自然すなわち混沌にある特殊な秩序をもたらすことが作品成立の契機となろう。おそらくここでいう「コントロールできないもの」とは、その他者たちが無秩序に作品を変容させていくということではなく、その作品の中にいる他者たちの知覚世界や環世界を作家がコントロールできない/しないことであろう。すなわち作者の想像力を超えたところに在る、作家の思考の地平を超える何かをもたらす存在という意味での「完全なる他者」である。

狩野が今回のプログラムテーマ「吃驚」について、「『びっくりは僕ではなく外側から与えられる』ための舞台を作る」(4)という言葉で受容していることから考えれば、作家が作品として作り出すものはその枠組みということになるだろう。それは作家によって作られた任意の環境といえるのかもしれない。だが作品は変化を内包した常に開かれた状態にある。それは言いかえれば新しい体験の場、新しい想像を獲得する場として作品が作られているということであろう。

このように鳥や植物は作品として設定された世界を「徹底的に理解しないもの」その「分からなさ」の象徴として存在する。作家も鑑賞者も「理解不可能」な存在が、自ら「理解していると思っている」世界を否定し続けることで、世界は一度白紙に戻される。「それぞれの新しい体験は、新たな印象に対する新たな態度を引き起こす」(5)とは、前述のユクスキュルの言葉だが、作品を構成する日用品の名が剥脱され、作品としての意味が解体されていくのをみることは、それが何かとして新たに認識あるいは名付けられた瞬間に立ち会うのと同じことなのかもしれない。

ところで今回は会場管理の問題もあり、ここ数年狩野の作品にいた鳥が不在であった。そのことは作家にとっては不本意なことであったかもしれないが、鳥がいないことは別の印象と鑑賞体験をもたらしたように思えた。確かに鳥は、その存在故に見る者に観察を促す。だが時に鳥の存在感が強すぎて、植物もインスタレーションも全て鳥のためにあるようにすら思えてしまうのだ。しかし今回はその鳥がいないために鑑賞者は、より中立的な立場に置かれた。不在の鳥を想像することで作られたインスタレーションを鑑賞するためには、人々は作品の中をより自由に/不自由に歩き回ることとなった。しゃがんだ先にある景色、覗いた所にある狭間、飛び越えなければならない障害物は、目の前の鳥という特定の存在ではない視点を体験的に鑑賞者に与えた。

また今回は鳥に焦点を強要されることがなかったことで、鳥にとっての○○という名すらつけられない茫漠さが作品に与えられ、空間におかれたモノたちはより抽象的な色や形として広がり、作品の響き合うような連鎖的な関係性がより繊細にあらわれた。空間の何らかの特性をきっかけに構成されたギャラリー内部のインスタレーションは、上部の窓から野外ステージへとつながり、それらは外の風景と地形をきっかけにさらに宿泊棟の屋根へと延びていった。この「つながる」ということも狩野の作品では重要な要素でもある。建築に寄り添いながら広がるそれらは、構造的であるが構築的ではなく、理論や秩序ではなく即興的かつ経験的な方法によって、微妙なバランスでつながっていく。それらはさらに外界の動植物の訪問や自然の変化によって連鎖的に歪み、たわみ、豊かな連鎖と繊細な均衡の姿を見せることとなった(fig.4)。

狩野はこうした連鎖を通常の関連性を失わせることで示そうとする。それはインスタレーションが見たこともないような形状をしていたり、見たこともないような素材によって作られていたりするのではなく、我々が日常的に使うもののうち、ある特定の目的のために作られた物が使用されていることとも関連しているように思われる。つまりそのことが「見たこともないような」という、それすらある種人間に属する夢想を排除するとともに、目的がはっきりしているものだからこそ、その目的とは何の係わりも持たぬものたちが、その目的とはかけ離れた働きかけをすることが強調されるのである。それは通常の回路を切断し、何か別の回路とつなぎ合わせようとするようなことなのかもしれない。こうして作品としての≪自然の設計≫は、何ものかが認識されるその予兆に満ちた開かれた「場」となるのではないだろうか。狩野はそれを積極的に提示するのではなく、それを獲得するための観察の場あるいは待機の場を設定する。それは自然界で見られる均衡を閉じた形で再現する抽象的なアクアリウムのようにもみえた。

-----------------------------

(1) ユクスキュル/クリサート『生物からみた世界』、日高敏隆・羽田節子訳、岩波文庫、2005年。(Jakob von UEXKULL/ Georg KRISZAT, Streifzuge durch die Umwelten von Tieren und Menschen, 1934; 1970.)

(2) 狩野哲郎、2010年7月、Webサイト「cat’s forehead」のメールインタビューより。

(3) 2010年11月21日狩野哲郎レクチャー「何かについてのスタディ」での発言。

(4) 2010年9月狩野が筆者に提出したプランシートより。

(5) ユクスキュル/クリサート『生物からみた世界』、日高敏隆・羽田節子訳、岩波文庫、2005年、97頁。

撮影:山本糾

fig.1 《発芽-雑草/Weeds》インスタレーション/ミクストメディア、2004年。撮影:斎藤剛

fig.2 《それぞれの庭/Respective garden》インスタレーション/ミクストメディア、2009年。

fig.3 《自然の設計/Natureplan》インスタレーション/ミクストメディア、2010年。

fig.5 《自然の設計/Natureplan》ACACでのインスタレーション。

吃驚 BIKKURI

October 23 -- November 21, 2010.

KANO Tetsuro

狩野 哲郎

Natureplan, installation photo: YAMAMOTO Tadasu

Creating a place for signs

KONDO Yuki

Just because parent birds are constantly bringing food to their young, it does not mean that they are raising their babies out of love. Parent birds are born to feed living beings with big eyes and mouths wide open, which they happen to see in front of them as a result of their certain action and regard them as their offspring. Therefore, even if eggs were secretly replaced or the young of a different species bigger than their offspring were waiting for food with their mouths wide open, parent birds would feed them like their babies as if nothing had happened.

It is said that “Naturplan (plan of nature),” the title of KANO Tetsuro’s work, is quoted from a book written by zoologist Uexkull.(1) Every living creature has its own senses, and using their senses, they convert information to their convenience to interpret their surroundings, and take actions based on it. For example, a mole regards a fallen tree blocking a road, an obstacle in human life, as a cozy residence, and the tree also tempts ants’ appetite. Every living being has come to have their shapes, functions and organs through “natural design,” and in order to live in their cycles, every living creature senses their surroundings under the control of this natural design, and takes programmed actions.

Kano’s works are known for using animals and plants. He began to use plants in “Weeds,” one of his early works in 2004 (fig.1), and the process of growing plants was included. From “Respective garden” (fig.2) in 2009, bantams were added, and the number of coincidental factors in his work has increased so as to make more organic changes in his work.

“Naturplan” is the title that he has used these several years for the series. (fig.3) Kano talks about how he came to introduce birds and plants in his work: when he was learning of space-related functions, values and meanings, he became aware of the fact that everything was basically designed in the interests of human beings as well as the fact that a crack in concrete, that was a damage, considered negative to humans, but it could be “a place for plants to grow.”(2) This explains that Kano introduced them in his work as the medium for him to find out different significance and values in existing space.

In Kano’s installation, simple materials such as nets and poles, which are available at a home center, are collected and arranged for composing a place. The place appears to be filled with drawings made on three-dimensional space with colorful materials spread over the place. And animals and plants are introduced in that space. Apples placed in the work go rotten during the exhibition period, fall, drop viscous liquid, and they look “unsuitable” for the exhibition. At first, released birds peck at apples and seeds “displayed” beautifully, and damage the surface of a cone-shaped mountain. Soon they scatter droppings having digested the food. Plants and seeds on display put forth buds whenever the conditions are satisfiable, ignoring that they are exhibits, and they are pecked by birds. The place, which is sometimes badly littered, is cleaned and re-arranged properly by the artist to be maintained as an installation. In the installation that first appeared to have been completed, all elements in their own world coexit, having relations with one another and at the same time, without each other’s interference.

Kano regards these animals and plants in his work, which bring about accidental development, as “absolute others” and something uncontrollable.(3) It does not mean, however, that he thinks they will cause an unforeseeable incident or an uncontrollable state of the work. No matter what the method may be, nature approaches all beings physically as well as spiritually giving some sort of “control” and special order attributed to nature or chaos, so there is a chance for his work to be formed. Here, “the uncontrollable” does not mean that “others” transform the work without any order, but it means that the artist cannot or does not control the world of perception or cycling world of the others contained in the work. In other words, “absolute others” exist beyond the artist’s imagination, and they are beings that will bring something beyond the artist’s sphere of thinking.

Of “BIKKURI (wonder),” the program theme of this time, Kano said, “I’d like to create a stage where “it is not me to be surprised, but a surprise is given from outside.”(4) As he has thus understood the theme, what the artist creates is a framework. In other words, it is an arbitrary environment made by the artist. The work is kept open all the time entailing changes. The work is made to provide us with a place where we can acquire new experience or imagination.

Birds and plants are thus presented as symbols of “incomprehension,” as they “do not understand at all” the world that is set up as an artwork. If the artist and viewers both imagined the world that those incomprehensible beings might be comprehending, the world could be reset anew. As above-mentioned Uexkull wrote, “… each new experience entails a readjustment to new impressions,”(5) if you observe how animals and plants in the work are dealing with daily necessities contained in the work, you are probably witnessing the moment when those items are recognized or named as something new.

This time, birds that have been included in his work these several years were excluded from the venue due to the managerial difficulty. Perhaps the artist was not happy about it, but, without birds, different impressions and experiences of appreciation must have been made possible. Certainly, birds’ presence is so strong that viewers are tempted to observe. Sometimes, it is so strong that it seems the installation and plants look like mere addition for the sake of birds. As there was no bird this time, viewers were relatively in a neutral position. In order to appreciate the installation in which visitors imagined that there were some birds, they walked around the installation in comfort at some times but less comfort at other times. Visitors looked at the scene while squatting down, peeping through a narrow opening, and jumping over an obstacle, with viewpoints that must have been different if birds were there.

Since birds were not what the viewers focused on this time, the work was given an obscure enough image that it could not be named “so-and-so for birds.” Things arranged in the space were spread in abstract colors and forms, and connected relationships seemed to resonate subtly. The installation inside the gallery, whose composition was triggered by some kind of characteristics of the space, was connected to the outdoor stage through upper windows. Furthermore, it extended, triggered by the outside scenery and geographical features, to the roof of the lodging facilities. This “connection” is one of the important elements of Kano’s work. Those elements extending along the building are structural, not constructive, and are connected in delicate proportion not by means of theory or order but by spontaneous, experiential method. What is more, they are warped and bent like chain reactions by the visits of animals and plants from outside and through natural changes, showing enhanced connections and delicate balance. (fig.3)

Kano tries to show such a chain reaction by getting rid of ordinary relationships. It does not mean that his installation has such a form as you have never seen before or it is made of unfamiliar materials. It seems to be related to the fact that he chooses things made for specific purposes from articles of daily use. In other words, it is emphasized that he intends to use things whose purposes are obvious and approach them in a way far apart from their ordinary purposes, excluding what you think “you have never seen before,” or a kind of fantasy vested in human beings. You might say that he is trying to cut off a normal circuit and connect it to some different circuit. I believe that “Naturplan” as a work presents us an open “place” filled with signs of something that we will be able to perceive. Kano does not show it straightforwardly but he creates a stage where we can observe and wait. At the same time, his work looks like an abstract aquarium reproducing, in a closed form, the balance found in the natural world.

-----------------------------

(1) Jakob von UEXKULL and Georg KRISZAT, “Streifzuge durch die Umwelten von Tieren und Menschen,” 1934; 1970.

(2) KANO Tetsuro’s writing.

(3) November 21, 2010, Kano’s lecture on “Studying about something”.

(4) September 2010, Kano’s plan sheet turned in to the writer.

(5) Uexkull and Kriszat, “A Stroll Through the Worlds of Animals and Men,” Translated and edited by Claire H. SCHILLER, International Universities Press, Inc., New York, 1957, p.49.

photo: YAMAMOTO Tadasu

fig.1 Weeds, installation/ mixed media, 2004. photo: SAITO Tsuyoshi.

fig.2 Respective garden, installation/ mixed media, 2009.

fig.3 Natureplan, installation/ mixed media, 2010.

fig.5 Natureplan, installation at ACAC, 2010.