trans×form

10:00am - 6:00pm, July 27 - September 16, 2013 / Admission Free

Worapong MANUPIPATPONG

ウォラポン・マヌピパポン

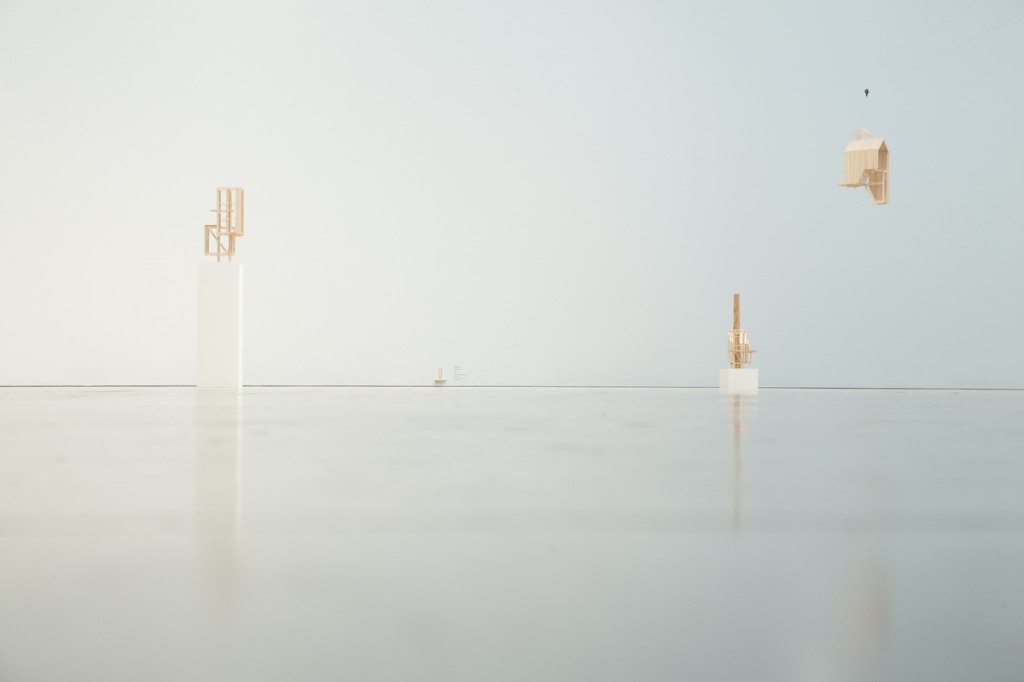

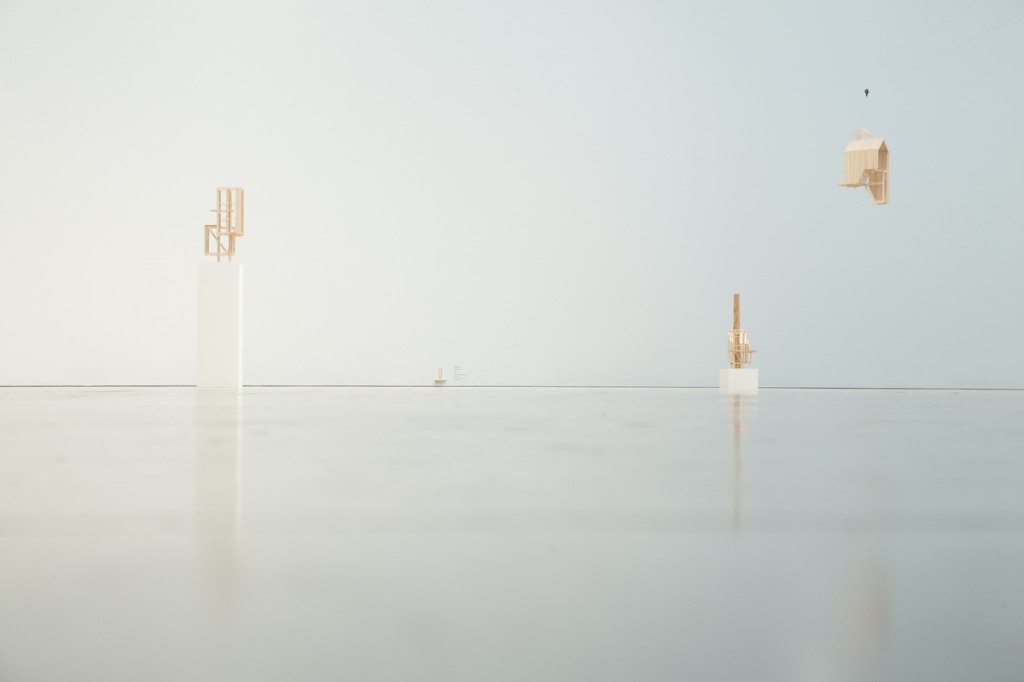

Hidden space #1 – 10, 2013

Dimension variable

Japanese cypress(Hinoki)

*10 small pieces were spread in ACAC.

Photo: OYAMADA Kuniya

Architectural Methods Based on Somatic Experience

HATTORI Hiroyuki

Worapong Manupipapong has enjoyed drawing since his childhood and so he aspired to learn fine arts in a university, but couldn’t obtain his parents’ approval, then he decided to study architecture, an interdisciplinary course between arts and science. He majored in interior architecture, the study of mainly interior spaces inside buildings, unfamiliar to Japanese people, and practiced interior design for two years after graduation. Due to the nature of interior design, his work only related to designing commercial buildings, and as he felt bored with that, Manupipapong went over to America to study basic knowledge of arts in general for about a year, laying the groundwork for practices across both disciplines, architecture and arts. Thereafter he studied architecture again in the Netherlands and Sweden, and came to create architectural works by his own hands, that is, minimal spaces regarded both as installation and as building, similar to his current works.

For this exhibition in Aomori, he made works classified roughly into three types, under the theme of minimal intimate space and space that anyone can create with their own hands. Let me firstly introduce a unit of work in response to his surrounding environment of Aomori centering on Aomori Contemporary Art Centre (ACAC). In a meeting held directly after his arrival at ACAC, Manupipapong made an impressive remark about his first impression; this building doesn’t have a face. After our walking through a narrow path in the forest, a circular building suddenly appears at a place where there is no sign of any building, but without a symbolic entrance, the path leads to an outside cloister passing down the middle of the building. We are spontaneously guided to inside the site, then inside the building, but we cannot readily find a front entrance that an ordinary building commonly features, that is, a point regarded as an architectural face. Indeed, there is no need for a splendid entrance to this building standing secretly in the forest, created under the concept of invisible architecture, but its face actually exists at a place different from the entrance door. Whilst enjoying rambling around this site which consists of three buildings, that is, the Exhibition Hall, Creative Hall as a stronghold for artists’ creation, and Residential Hall for accommodating them, Manupipapong discovered the spot to be considered as its face, in front of a path between Creative Hall and Exhibition Hall. The fact that the architectural face exists immediately before the path where artists pass, makes us to recognize that it is here that creation comes out. Manupipapong determined the spot as where we can appreciate this architecture further, and built here an arbor as a device to see landscapes by his own hands (fig.1). A Japanese red pine was set upright in the middle, surrounded with four poles, from which as a starting point two rooms were placed at the back and forth. In a forward direction from the arbor, we can see the whole image of the building reflected on the pond. The front room with the floor in a lower position looks to the Water Terrace of the Exhibition Hall (fig.2), but the rear room with the floor in a higher position looks out towards the forest (fig. 3). As sitting on the front floor, we directly face the Exhibition Hall, and a landscape comes into sight in a proper position. When entering this room, we hear a comforting song from the water basin before our eyes, because different sounds from the forward are integrated together due to roof structure converging into the recesses. On the other hand, when going up to the rear room in a higher position, the view changes completely, we see tall trees of the forest open out before our eyes, and the song of cicadas and insects rings out closer to our ears. It’s only two-meters difference in height of the floors that dramatically changes the environment that we can experience. The front room exists to see the contemporary architecture, and the rear room to feel the forest. The minimal structure offers us an experience of completely different environments.

At the present day when a computer can perform complicated structural calculations, many architects tend to develop structure itself as a radical expression. However, Manupipapong keeps a critical distance from contemporary architecture, pursuing the possibility for physical experience further than formative expression. He explores minimal space that anyone can create, suggesting that on the axis of basic structure we can build through our senses and experience.

Secondly, Manupipapong created microscopic buildings titled as Secret Space (fig.4). This work filled with his delicate and tender senses of environment is based upon his thorough observations. It is symbolic of the exhibition title, “trans×form”, succeeding in transforming scale and viewpoint admirably. As the title of the work shows, ten secret spaces were placed in ACAC. Manupipapong turned his thought towards the existence of alien creatures such as insects and small animals in this neighborhood, and created buildings to perceive ACAC as another world through their eye level. He put small stairs on a ventilation duct on a floor in the gallery to create a secret chamber under the floor (fig.5), installed a miniature window and door in a tree to bring the life inside the tree to mind (fig.6), inserted a lattice of sticks into a foot light, like a sliding screen window, to liken a lighting equipment to a house (fig.7), and placed miniature stairs between large books and a shelf, to invite us to imagine that the stairs lead to a sacred place (fig.8). Through dealing with such architectural icons and using these component parts as symbolic signs, he transformed ACAC into a city. The pieces prompt us to imagine how small living creatures experience this megalopolis from their eye level, triggering another perspective on other beings and different life styles. By imagining the world on a completely different scale of creatures with an extremely different sense of value, we are reminded that cities and societies with alien value systems exist nearby, and spontaneously turn our attention to this. These miniature works tenderly demonstrates the fullness we can feel by thinking from a viewpoint of such a different beings and accepting it. In Gulliver’s Travels, Jonathan Swift narrated the process that Gulliver experienced through both hardship and happiness. In countries of both midgets and giants he reveals that many things alien to us exist, which seems as if he critically satirized the then society, denying that the United Kingdom is the only absolute existence. In Secret Space, Manupipapong also appeals for a diversity of the world seen only when standing at the eye level of the alien creatures that we cannot readily get, through brilliantly transforming scale. These small buildings are almost a boundary between another world and the viewers.

Lastly, let me introduce artworks Manupipapong created in addition to works above, in the latter half of the exhibition. This piece asks a sharp question about practicing architecture. There are several wooden structures such as a wooden decked amphitheater and bench installed outside in ACAC. These are what Manupipapong paid attention to. For example, he stripped the three-millimeter-thick dingy surfaces from a worn bench, and converted them to an almost full-length drawing (fig.9). To be specific, as if presenting an isometric drawing[i], he rearranged stripped surfaces on the wall, at the same position like a skin stripped from the seat to draw a seat, and a skin from the leg to draw a leg, and finally completed a two-dimensional drawing from a three-dimensional object. That is to say, an isometric drawing resembling a three-dimensional object was extracted from the object. The drawing has a three-dimensional effect and material presence more than an original object stripped of its surface. The bench without its skin looks astonishingly smooth and flat. This confuses our somatic sensation with a focus on sight.

In The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception[ii], J. J. Gibson remarks, in referring to replicating and copying, the terms “copy”, “replicate”, “duplicate” and “image”, however familiar, are vague and slippery. The four terms above cannot exactly express Manupipapong’s action of transforming an object to a plane surface on a scale of 1 to 1, but his action reflects all of the aspects of these terms. These slippery artworks show how to give exact description of a building, as well as his unique depiction. He explores how to perceive space in a more direct and exact way through drawing with skins of an object on a scale of 1 to 1.

What is architecture? What does it mean to exist as a three dimensional object or as drawing? What is to be a real thing? What does it mean to actually exisit? These are some of the questions that the artworks provoke. The works question our perception and the recognition of human beings through drawing full-length space, appealing to human somatic sensation. At times Manupipapong offers a critique of architecture, other times he prompts us to consider the diversity of the world. He also raises a doubt towards human perception, through practicing all architectural actions based on our own somatic sensation. He keeps a broad-minded and flexible approach to his practices at all times, accepting and responding to the landscape before his eyes.

[i] Isometric projection is a method for visually representing three-dimensional objects in two dimensions in engineering drawings. It’s a kind of axonometric projection in which the three coordinate axes appear equally foreshortened and the angles between any two of them are 120 degrees.

[ii] James J. Gibson The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception, Saiensu-sha Co., Ltd. 1985

***

Photos of the works made in ACAC

Exhibition View

Exhibition View

3.5 tatami mat room, 2013

3.5 tatami mat room, 2013

W2600xD2700x3600mm

Pine timber, Stainless screw

1/10, 2013

1/10, 2013

W280×D320×H500mm

Japanese cypress (Hinoki)

Life size isometric drawing #2, 2013

Life size isometric drawing #2, 2013

Dimension variable

Existing material of wooden deck

※Exhibited from September 2

Life size isometric drawing #3, 2013

Life size isometric drawing #3, 2013

Dimension variable

Existing wooden bench

※Exhibited from September 2

Deconstructed composition #2, 2013

Deconstructed composition #2, 2013

Dimension variable

Reclaimed wood

※Exhibited from September 2

Hidden space #1 – 10, 2013

Hidden space #1 – 10, 2013

Dimension variable

Japanese cypress (Hinoki)

*10 small pieces were spread in ACAC.

All photos are taken by OYAMADA Kuniya

Worapong MANUPIPATPONG

fig.1 - fig.3 3.5 tatami mat room, 2013

W2600xD2700x3600mm

Pine timber, Stainless screw

Hidden space #1 – 10, 2013

Dimension variable

Japanese cypress (Hinoki)

Life size isometric drawing #1, 2013

Dimension variable

Existing wooden bench

All photos are taken by OYAMADA Kuniya

trans×form ─かたちをこえる

2013年7月27日(土)~9月16日(月・祝) 10:00-18:00 / 無料

air2013-2ja

ウォラポン・マヌピパポン

Worapong MANUPIPATPONG

《秘密の空間 #1-10》、2013

サイズ可変、檜(※敷地内10か所に小さな作品を設置。)

撮影:小山田邦哉

身体経験に依って立つ建築術

服部浩之

子供の頃から絵を描くことが好きだったウォラポン・マヌピパポンは大学進学時に美術の道を志したが両親の賛同を得られず、芸術と科学が融合した領域である建築を学ぶことを選んだ。彼が修めたのは日本ではあまり馴染みのないインテリア・アーキテクチャーという主に建築の内部空間を探求する学問であったため、卒業後2年間は内装設計などの仕事に従事した。内装設計という性質上商業建築の設計が主で、それを退屈に感じたマヌピパポンはアメリカに渡り約1年かけて芸術全般の基礎を学び、建築とアートの領域を横断する活動の礎を築いていった。その後オランダとスウェーデンで再び建築を学び、現在のようなインスタレーションと建物のどちらにも捉えられる最小限の空間を自らの手で生み出す建築作品をつくるに至った。

青森では、最小限の親密空間と誰もがその手で生み出せる空間をテーマとし、大別して3つの異なる作品を制作した。最初に紹介するのは、国際芸術センター青森(ACAC)を中心とした青森という彼を取り囲む環境への応答として生まれた作品群だ。マヌピパポンはACAC到着後の最初のミーティングで、第一印象として「この建築には顔がないと思った」という印象深いひと言を残した。森の小径を抜けると、建物の気配など全くなかったところに突然円形の建築が出現するのだが、象徴的なエントランスなどはなく、小径から続くように建物の中央を突き抜ける外部回廊に至る。いつの間にか敷地内に、そして建築内に導かれ、通常の建築が持つ正面、つまり建築の「顔」となるポイントがすぐには見当たらない。確かに「見えない建築」というコンセプトのもと森にひっそりと佇むこの建築には華々しい玄関など必要ないが、その顔は玄関口とは別の場所に存在する。展示棟以外にも、アーティストの制作活動の拠点となる創作棟、そして彼らが生活する宿泊棟が存在し、その三棟が散在するこの施設をマヌピパポンはのんびりと巡り、創作棟から展示棟へと至る小径の前に顔となる場所を発見した。アーティストの日々の通り道の目前に建築の顔が存在するのは、ここが創造の現場であうということを再認識させてくれる。マヌピパポンは、その場所をこの建築をより深く味わえる場所と見定め、そこに風景を見るための装置としての東屋を自らの手で建築した(fig.1)。直立する1本の赤松の木を中心に据え、その周囲に4本の柱を建て、それを起点として前後にふたつの部屋が設置されたこの東屋の正面には、水面に投影される建築の全容が浮かびあがる。手前の部屋は低い位置に床面を設え展示棟の水のテラスに向けて開かれており(fig.2)、背後の部屋は高い位置に床レベルが設定され、森に向けて開かれている(fig.3)。手前の床に腰をかけるとちょうど展示棟の建築に向き合う体勢となり、その風景がほどよい高さで眼に入ってくる。この部屋の内側に入ると目の前の水盤の水のせせらぎがとても心地よく耳に響いてくるが、これは奥に向かって収束する屋根の小屋組みにより正面の音が集約されるためだ。一方で奥の高い部屋に上ると、景色が一変し森の高い木々が眼前に現れ、蝉や虫の声もより近くで響いてくる。ほんの2m床面が上昇するだけで、経験できる環境が劇的に変わる。現代建築を眺める前面の部屋と、森を感じる背後の部屋。最小限の設えにより私たちが経験できる環境は劇的に異なったものとなる。

コンピュータにより複雑な構造計算ができるようになった現代では、多くの建築家が構造そのものを先鋭的な表現として探求する傾向がある。一方で、マヌピパポンは現代建築に対して批評的な距離感をとるかのように、人が感覚的・経験的に築くことができる基本的な構造を軸に、形態表現よりは人の身体的な経験がどれだけ豊かになるかを追求し、誰もがつくりだすことができる最小限の空間の可能性を追求している。

次にマヌピパポンは、《秘密の空間》というミクロ建築群を制作した(fig.4)。彼の徹底した観察と、環境に対する繊細で優しい感覚が溢れる作品だ。まさにtransXformを象徴するもので、見事なスケールと視点の変換が成されている。ACAC内10ヵ所に設置された密やかな空間だ。マヌピパポンは周辺に暮らす昆虫や小動物など異なった生物の存在に想いを巡らせ、彼らの目線でACACをひとつの別世界として捉える建築群を生み出した。ギャラリー床面の換気ダクトに小さな階段を架けて床下の秘密部屋を生み出したり(fig.5)、一本の木に小さな窓やドアを装着してその木の中の暮らしを想起させたり(fig.6)、足下灯に格子を入れて障子窓に見立て照明器具を家屋に見立てたり(fig.7)、本棚の大型本の隙間に階段を挿入して、その先に神聖な空間があるように思わせたりと(fig.8)、建築パーツのアイコンを象徴的な記号として扱い、ACACをひとつの都市世界に仕立て上げた。小さな生物が如何なる目線でこの巨大な都市を経験しているのかを想像させるなど、他者や異なった生活に眼を向ける引き金となっている。価値観が全く異なるものの極(きわみ)としてスケールの違う生き物の世界を想像させることで、異質な価値観の都市や社会はすぐそこに存在すること想起させ、そこに眼を向けること促す。そしてそのような異なった存在の立場から考えてみることや、それを受け入れることで手に入れられる豊かさを、優しく示している。スウィフトは『ガリバー旅行記』のなかで、ガリバーが小人の国や巨人の国を経験し様々な苦難や幸福を得る過程を描くことで、自分とは異質なものが多数存在することを示し、英国だけが絶対的な存在ではないとでも言うように当時の社会を批判的に風刺していると思われるが、マヌピパポンは《秘密の空間》において自分が容易には到達できない異質な存在の目線に立ってみることで見えてくる世界の多様性を、スケールを鮮やかに変換することで訴えかけてくる。この小さな建築は異世界と鑑賞者をつなぐひとつの境界でもあるのだ。

最後に、マヌピパポンが展覧会期後半に追加制作した作品を紹介したい。この作品は建築することへの鋭い問いを投げかけてくる。ACACには野外ステージのウッドデッキや屋外設置のベンチなど木製の構造体がいくつか存在する。マヌピパポンはこれらに着目した。例えば長年利用され表面が黒ずんだベンチの表面を厚さ3ミリくらいできれいに剥ぎ取り、それをほぼ等身大のドローイングに変換した(fig.9)。どういうことかと言うと、剥ぎ取った表皮を、座面は座面、脚は脚として同じ関係で壁面にアイソメトリック[i]を描くように再配置し、三次元の立体から二次元のドローイングを描出したということだ。つまり立体から、立体のように見えるアイソメのドローイングを分離産出したのだ。そのドローイングは、表面を剥ぎ取られたオリジナルの立体よりも立体感と物質的存在感を備えている。表皮を失ったベンチは、非常にのっぺりした存在になる。これは視覚を中心とする身体感覚に混乱を与える。

J・J・ギブソンは『生態学的視覚論』において、模写すること、写すことに言及する際に、「写し(copy)、模写(replica)、複写(duplicate)、像(image)といった言葉は、見慣れたものだが、意味は明確ではなくつかみどころのない言葉である」と述べる[ii] 。マヌピパポンの立体を1/1で平面化する行為は、上述4つのどのことばも正確には言い得ていないが、一方ですべてのことばに含蓄されるものを備えている。このつかみどころのない作品群は、建築を正確に写し取り記述する(description)方法であるともに、彼独自の表現(depiction)でもあるのだ。彼は物質の表皮を用いて1/1のドローイングを描くことで、空間をより直接的に正確に知覚する方法を探求する。

建築とは、立体とは、ドローイングとは、本物とは、そして実在するとはなにか。様々な疑問をこの作品は投げかけてくる。等身大の空間を描くことで、人の知覚や認識について問いを投げかける人間の身体感覚に寄り添った作品だ。マヌピパポンは、すべての建築行為を私たち自身の身体感覚に依って立ち実践することで、ある時は建築への批評的態度を表明し、ある時は世界の多様性について思考するきっかけを提示し、そしてまたある時は人間の知覚認識そのものに疑問を投げかけてくる。その背後には目の前の風景を受け入れ応答する、おおらかで柔軟な開かれた態度がいつも存在することを忘れてはならない。

《3.5畳の部屋》、2013

《3.5畳の部屋》、2013

W2600xD2700xH3600mm

松、ステンレスネジ

《1/10》、2013

《1/10》、2013

W280×D320×H500mm

檜

《等身大のアイソメトリックドローイング(等角投影図) #2》、2013

《等身大のアイソメトリックドローイング(等角投影図) #2》、2013

サイズ可変

既存のウッドデッキ用木材

※9月2日より展示公開

《等身大のアイソメトリックドローイング(等角投影図) #3》、2013

《等身大のアイソメトリックドローイング(等角投影図) #3》、2013

サイズ可変

既存の木製ベンチ

※9月2日より展示公開

《脱構築されたコンポジション #2》、2013

《脱構築されたコンポジション #2》、2013

サイズ可変

廃棄木材

※9月2日より展示公開

《秘密の空間 #1-10》、2013

《秘密の空間 #1-10》、2013

サイズ可変、檜(※敷地内10か所に小さな作品を設置。)

撮影はすべて小山田邦哉

ウォラポン・マヌピパポン

上からfig.1-fig.3《3.5畳の部屋》、2013

W2600xD2700xH3600mm

松、ステンレスネジ

上からfig.4-fig.8《秘密の空間 #1-10》、2013

サイズ可変、檜

fig.9《等身大のアイソメトリックドローイング(等角投影図) #1》、2013

サイズ可変

既存の木製ベンチ

撮影はすべて小山田邦哉