Storyteller – Units of Recognition

November 3 (Sat) ~ December 16 (Sun), 2012 10:00 - 18:00 / Free

YU Cheng-Ta

A Practice of Singing: Japanese Songs, Installation view

Distance Between Those Who Communicate

KONDO Yuki

YU Cheng-Ta’s video works contain unique humor. The humor arises from various gaps that he reveals in his works. The gaps are subtle differences between similar people rather than a wide gulf, but decisively separating them. Although his works make the “differences” noticeable, they are not considered negatively as severance, but instead present a basis to accept different types of variations, by adding a spice of humor.

Yu often uses a “language” to reveal gaps and differences. It is a means to convey a certain message, appearing in forms of narration, songs, explanation or body language in his works. There the language often carries “mis-” like mistakes or misleading, representing imperfect state as a communication tool. It is fact that a language is ambiguous, for example they don’t always convey all messages without a single mistake even in conversation between people using the same native language. On the other hand, they occasionally convey a certain message correctly despite using a broken language in conversation. It is a message beyond words, silence and gesture as well, that determines whether or not you can understand the messages. Though Yu uses a volume of “language” in his works, he does not care much for a language itself, but rather he aims to prompt viewers to reconsider distance or the relationship between oneself and others through humorously revealing gaps which arise in a situation, or communication involving utterance of language.

In the piece titled A Practice of Songs: Japanese Songs which resulted from this residency program, Yu practiced Japanese songs as shown in the title and created a music video in the Karaoke style. According to him, Taiwan has been strongly influenced by Japanese pop culture and it was flooded with Japanese popular songs and their Taiwanese versions in his childhood. But “famous Japanese songs” to Yu were not always the same as familiar songs to us, Japanese, due to a few-years delay of covering Japanese songs in Chinese caused by issues on copyright, as well as due to difference in taste. At that, Yu selected 5 obviously famous Japanese songs in Japan, from famous “Japanese songs” in Taiwan, according to the result of his survey targeting his surrounding people. Here is the first gap coming out. Though pop culture seems to be a medium for connecting Taiwan and Japan who are neighboring cultural regions, there are subtle differences arising from time lag and difference in taste, reminding us of both nearness and distance in culture, language and geography.

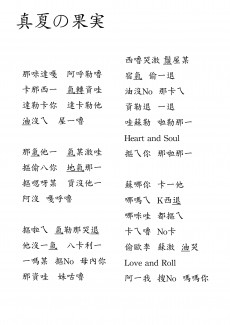

Then Yu wrote lyrics on sheets, converting Japanese into the Roman letters in order to practice songs, because he cannot read Japanese at all. But it was very difficult for him to read foreign words written in the Roman letters, and so he converted them into the Chinese phonograms (fig.1). It looks as if you write down an English song in Katakana, then read and sing it; “I love you” to be changed into “アイラブユー”. It is inevitable that the lyrics cannot reproduce the original pronunciation correctly. Yu practiced again and again, and sang in all seriousness but you can easily find slips of the tongue and errors in converting sounds in a finished music video. Though Japanese lyrics flow, like a Karaoke video, in the lower part of the screen where Yu is singing, they are not the same as the original but words that a Japanese speaker wrote down whilst listening to his song, and thus partly containing a meaningless list of words (fig.2). Because the songs are well-known to us, our brain can guess correct passages from the context and on our advance knowledge of the lyrics, perceiving slips of the tongue as just inarticulate utterance in the case of listening. However, through transforming into letters, they were recorded as nonsense words that we cannot understand even if reading them. Here is the second gap arising; difference in pronunciation between those who speak different native languages as well as difference in meanings communicated through the pronunciation.

In order to create the music video in the Karaoke style, Yu sang songs using apparent gestures of those who sing in Karaoke, in front of tourist attractions of Aomori prefecture because such attractions are often chosen as locations despite appearing out of the context in music videos of Karaoke. His video works evoked a laugh by errors in pronunciation, slips of the tongue and deceitful screens imitating Karaoke perfectly.

By the way, does the piece of A Practice of Songs: Japanese Songs cause those who don’t understand Japanese the same kind of laugh as Japanese viewers? Even though they cannot understand Japanese, they would join in the laugh by the elaborate atmosphere of music videos in the Karaoke style, the way that Yu sings overacting like an enka-singer and his skillful singing voice. But his small slips of the tongue are somehow humorous not only because of his incorrect pronunciation, but also because each error reminds us of another word, possibly conveying different messages. That’s why you may need some knowledge of Japanese to understand the works.

Yu says that he creates “site-specific” video works suitable for a place where the works are exhibited, in order to deal with such subtle differences in language and culture [1]. Though his works may not always receive “international” or even “universal” reactions from the viewers, because they deal with subtle gaps in communication, Yu intentionally chooses the gaps revealed only by such a way, calling the works “site-specific”. In addition, Yu intends to reveal the gaps and differences in communication not only through errors in language and pronunciation, but also through structure of video or visual image.

Yu often deals with the relationship between what is in front of the camera and what is behind, or between sender and recipient of “images”. Most of his works have a form in which Yu comes in directly or indirectly and he or someone else gives a speech to viewers who are supposed to be watching the video. A kind of backside process is also revealed there from the viewpoint of those who send messages. For instance, in the piece of A Practice of City Guide: Auckland, Yu impersonates a local reporter and excitedly explains tourist attractions of New Zealand to “viewers” supposed to be in front of a monitor (fig.3). In fact, he just reads texts written by a local person, not conveying his own knowledge of contents. Of course, he just does it toward a camera, not speaking to someone else. The video reveals a dim relationship between sender and recipient of message by the ambiguous subject, using the framework of visual media and viewers forcing us to accept, without any doubt, the fact that three roles separately exist; those who control the contents, those who write the texts and those who just act. Both the gap in communication shown in the movies and the media’s peculiar gap revealed by structure of works subsist in Yu’s works, sometimes adding critical and political color, consciously or unconsciously, as well as humor.

Such structure also exists in the piece of A Practice of Songs: Japanese Songs. A monitor screen is evenly divided into two images, showing Yu singing using gesture with a cassette player on the left, and an assistant holding up a lyric sheet in front of Yu on the right (fig.4). In other words, this piece also shows both of the resultant image usually shown on the front and the backstage producing the “finished works”, at the same time. Apart from these video works, he displayed various items revealing the process involved in creating these “finished works” as part of the exhibition; Chinese versions of Japanese songs that his first inspiration came from, unused lyric sheets in Roman letters spelling pronunciation, lyric sheets that he actually used and a conversion table for Chinese phonograms (fig.5). The process also represents that of converting and translating language and culture.

Even the “finished works” also retain something imperfect containing a lot of mistakes. It also reminds us of a kind of clear barrier or gap between two languages or two cultures appearing in the process of conversion and translation. Additionally, lyrics converted into Chinese phonograms by Yu flow on the right image, and on the left lyrics spelling exactly Yu’s slips of the tongue and errors in pronunciation as mentioned above. In other words, we only have difficulty in correctly understanding messages of the song from both images. There the Japanese song supposed to be under a common knowledge to those who understand Taiwanese, those who understand Japanese and those who understand the both, was converted to a meaningless list of words or sounds that cannot convey any message correctly to all, through the intervention by YU Cheng-Ta.

Even though that is exactly true, we can enjoy guessing the song, correctly or wrongly, from the context, through our own knowledge or by the way Yu overacts. By showing both, Yu does not only make the presence of language barriers clear, but also suggests a possibility to get over it. Apart from translation, our communication always fills with severances and discrepancies, and it is probably impossible to accomplish a perfect communication, but transmission is done. Yu’s works reveal gaps in language and communication, while tolerating mistakes and discrepancies with humor, and the open “language” can gain a possibility to develop further communication. There he would not consider discrepancies in communication negatively, accepting the communication containing a lot of errors with positive attitude.

[1] YU Cheng-Ta’s remarks in his lecture, “Language Shifter” on November 25, 2012.

Translated by NISHIO Sakiko

©YU Cheng-Ta

©YU Cheng-Ta