Courage in Transience

July 27 (Sat) – September 8 (Sun), 2019, 10:00-18:00, admission free

Gianfranco FOSCHINO

Immersed in Movement

MURAKAMI Aya

"Where does the Aomori snow go?" (*1) This was the question Gianfranco FOSCHINO asked upon accepting my offer to join Courage in Transience. Foschino first visited Aomori in March 2018 during heavy snowfall and was working on artwork involving water, which made this a very natural question. Beyond that, however, I think that his question revealed something about the consistency in his approach. Foschino’s residency, which began in early June, did not focus on mere fact-finding in the area but placed emphasis on being present in a place, taking the time to truly observe it. He would begin filming from before dawn and would repeatedly visit the same locations, including the Oirase Gorge and the forests that surround the ACAC. He would then pore over his footage, spending hours deliberating before experimenting over and over with the arrangement of the gallery. His personal engagement with time and space is similar to what he conveys through his work.

Upon entering the gallery, the first thing the audience sees is video sculpture MIZUNOME(*2). Just past the entrance, a stream of water seems suspended in the darkness. A single glass sheet, well above a person's height, rises vertically, supported on both sides by concrete blocks. Ripples repeatedly melt away just as soon as they form some indistinct shape or pattern. The audience is entranced by the water’s continuous movement, unable to look away. This is perhaps because the water seems to flow not vertically from above but out toward the viewer(*3), as if it would flow straight into their body. It reminds us of the water cycle, as well as the water crisis, as snow melts and flows into the rivers, seeps into the soil, becomes spring water, and enters our bodies. Here, we could say that Foschino is incorporating the body of the viewer into his iconic work as a type of media.

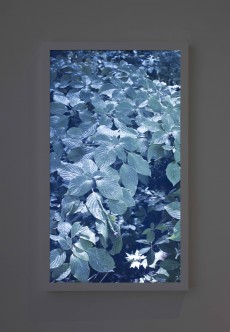

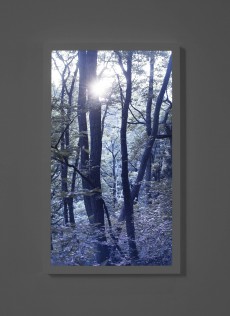

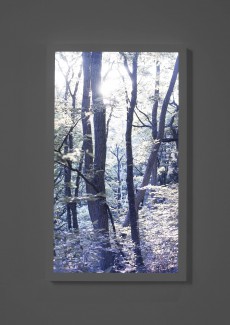

Next, the audience moves on to MITSU(*4), at back right, and MORI(*5), located beyond MIZUNOME inside the gallery space. With both MITSU and MORI, the viewer is drawn toward a white frame that seems to hover in front of the white gallery wall. At first, the viewer is looking at what appears to be a photograph or painting, but moving closer to inspect its slight but certain movement, the viewer is alerted to the fact that they are actually looking at a video. MITSU portrays, through a dim screen, video of a thicket of silvery shining leaves rustling in the wind. MORI is a video work shot with the camera facing the sunset, capturing the sunlight as it falls through the forest.

AME GA HURUMAE (*6)is exhibited in the small room at the end of the arc-shaped gallery. The video captures subtle changes in the mist that appears in a valley in summer. As it moves to and fro, the mist blurs the contours of the trees, obscuring the depth of frame. In the imperceptibly slow rise of the early morning light, only the occasional rustle and sway of the leaves give certainty to the passing of time.

Foschino has previously used fixed-point photography to present video works that present natural and urban landscapes in real time. By developing his work as video installations, he is now also giving consideration to the frame of the image. First of all, throughout the exhibition, the audience is encouraged to actively watch these movements, though many of us have grown accustomed to expecting—and demanding—stimulation from videos. In general, while video is often presented in widescreen, Foschino aims to deviate from that frame by employing tall vertical screens. On the other hand, by putting screens inside white frames in dialogue with paintings and photographs, he emphasizes that video is a medium created for the observation of movement. But his larger-than-life video sculpture is more than a window into the world within the frame. Rather, it acts as a portal, immersing not just the viewer’s eyes, but their whole body, into the work.

Furthermore, it may be a rhythm that allows the viewer to enter the work with their whole body, a rhythm born from the beauty of the fleeting compositions that appear on the screen, moment after moment. Even a casual viewer, before they know it, will be drawn into the video as if it were music. In MITSU, this is realized as time passes languidly, in the glint of light on the sparkling leaves and the depth that it reveals. In MORI, this is achieved as the sun slowly sets, illuminating the flying insects, spider webs, and colors of light that fill the audience’s vision. The spectacle and eccentricities of video do not enslave us. No, as we watch, we are able to sense even the subtlest, most delicate of changes, fueling an inquisitive desire to see what will happen in the next moment.

In these videos, scenes of moments past are presented in all their complexity. The many compositions of light and color that exist within a single scene continue to shift with every second at their natural pace. Light pours in from the windows and reflects on the arc-shaped wall as well, entering into the frame and adding to the complexity of the video installations as the light in the gallery is constantly changing. MIZUNOME, too, introduces additional complexity using light as it passes through and reflects off the glass and on the gallery floor, the texture of the concrete, and even the very shadow of the viewer.

It is important to note that this natural light also pours into the viewer's own body. By emphasizing sculpture and three-dimensional elements using video, a medium that fixes time and space in a certain way, Foschino demonstrates the moving image in a spatial relationship, creating a state that is connected to the body of the viewer. Put differently, the viewer is driven to confront their own complex world as they notice both complexities within the video—somewhere in the past—and complexities within the gallery space—here and now.

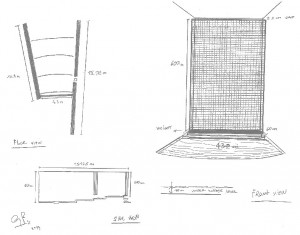

Finally, I would like to touch on works that were inspired by ACAC but were never realized.(*7) Foschino was planning an installation where a large white net would hang in the space between the exterior wall of Gallery B and the concrete wall across the ACAC’s water terrace. The white net would blur the scenery beyond, as if it were an abstract painting. Here Foschino would not project any moving images. Instead, the white screen itself was intended to heighten our sense of sight.

In other words, Foschino’s creativity cannot be bound to any one medium. In order to explore modes of expression that let people be aware of the things they see, Foschino continues to present works in dialogue with physical space and all of its ever-changing facets. What I can say is that the true value of his efforts will appear only in that heightened state of sensitivity that can only come from experiencing his works firsthand.

(*1)Correspondenece by email before his residence began.

(*2)MIZUNOME means “eyes of water” in Japanese.

(*3)Due to the fact that the video was shot at an angle rather than parallel to the water’s surface.

(*4)MITSU means “dense” in Japanese.

(*5)MORI means “forest” in Japanese.

(*6)AME GA HURUMAE means “before the rain” in Japanese.

(*7)Concept Sketches detailed in below.

(translated by Queen & Co.,Ltd.)

MIZU NO ME

Video sculpture

HD rear-projection on glass, concrete, steel, rear-projection film, 18 min, color, silent, loop, 190 x 280 x 140 cm,

2019

MITSU

Video installation

60" LED screen with white wooden frame mounted on wall,

HD, 28 min, color, silent, loop

MORI

Video installation

50" LED screen with white wooden frame mounted on wall,

HD, 16 min, color, silent, loop,

2019

AME GA HURUMAE

HD projection on wall inside a dark room

28 min, color, silent, loop,

2019

above all photo: YAMAMOTO Tadasu