Ubiquitous Views

10:00am-6:00pm, July 30 — September 11, 2016/ admission free

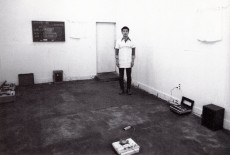

KAMIMURA Yoichi

上村洋一

"SOMEWHERE"

Landscapes,sound,speaker,2016

photo: YAMAMOTO Tadasu

Listening to the self through artificial landscape: The field recordings of KAMIMURA Yoichi

KANEKO Tomotaro

KAMIMURA Yoichi often uses field recordings in his works, such as in SOMEWHERE, which combines a painting of the Aomori landscape with sounds of the place where it was drawn, and perfect circle, which uses the sound of waves in the new and full moon in a room where the light constantly changes. In recent years, this method of recording natural sounds outdoors has been at the center of his production. Kamimura, who trained as a painter, also made music alongside his studies and has always incorporated the relationship of sound and vision and the recording of sound as themes in his work. In earlier artworks, Kamimura experimented with sound recordings in various modes and forms. Some examples include his Conductor of Scenery series (2010), which uses video as a musical score; his twilight message series (2010), which is an example of onomatopoeia, language’s mimicry of sound, molded into art; and night passage (2011), in which Kamimura constructs composer Erik SATIE’s pieces and accompanying sheet music as an installation. Field recordings have become the core of Kamimura’s work since night boat (2012), which documents a boat drifting in the ocean at night. For example, grandmother, prologue (2015) combines the soundscape of his daily life with a fictional account based on his grandmother’s memories of living in Manchuria. For 0°C (2016), together with artist UMEZAWA Hideki, he collected sound recordings of ice from artists all over the world.

According to sound art theorist Caleb KELLY, since the turn of the century, there has been a trend in sound art to combine field recordings with video and installation.[1] Kelly points out sound artist Stephen VITIELLO as a leader in the genre, best known for his World Trade Center Recordings, which he made in 1999 as a resident artist living on the 91st floor. Vitiello captured the vibrations of the building itself using contact microphones and then converted them into sound. Recording at such height far above the ground made the microphones more susceptible to the effects of weather and nearby aircraft. His 2007 recording Listening to Donald Judd took a similar approach, this time using as a sound source Judd’s outdoor sculptures in Marfa, Texas.

Listening to Donald Judd and Kamimura's SOMEWHERE are thematically similar as field recordings in that they both make use of existing artworks, but the sounds of the two pieces are totally different. Vitiello’s is mainly abstract noise, like a quiet moan converted from vibrations of minimal objects minimal stereoscopic vibrations caused by an environment. What we heard in SOMEWHERE are concrete sounds that evoke imagery of the recorded landscape—the chirp of birds and cicadas, the hiss and gurgle of sulfur gas, and the sound of a cable broadcast, among others. They could be thought of as background music or the soundtrack to the landscape paintings.

Kamimura's artwork, however, seemed to focus on the contrast between painting and recording rather than the ambiguous connection between the two. Speakers for background music are usually placed inconspicuously, out of sight, but the speakers and cables of SOMEWHERE are strewn across the floor in plain view, insisting on the existence of a different order from the visual world. The landscape paintings each show separate worlds within their frames, but sound blends together within the space. As the audience experiences the space, they combine the individual landscapes with sounds from completely different places. These visual and aural differences bring to mind all of the contrasting relationships that comprise SOMEWHERE. Recordings made by hand and recordings made by machine. Past and present. The experience of the landscape painter and the experience of Kamimura himself. What connects these contrasting elements are concepts of location and landscape, of records and memories. However, might SOMEWHERE express recording and location as essentially fragmented entities? If the eyes and ears (not to mention the nose, tongue, and skin) render their own distinct shapes of memory, then it may be nothing more than coincidence that we experience personal memory as the convergence of these sensory memories. In grandmother, prologue, too, Kamimura superimposes the contrast of sound and vision with the contrast of other people’s experiences.

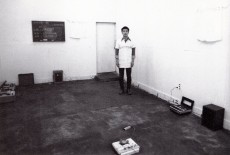

SOMEWHERE causes me to ponder the formation of experience. In this sense, I feel it shares commonalities with sound art in 1970s Japan, when artists used sound recordings in an attempt to observe the mechanisms of the senses. HIKOSAKA Naoki, known for his Floor Event (1970), played a recording of the sea atop a roof with SHIBATA Masako in SEA FOR ROOF (1972). WADA Morihiro played different messages from multiple sound recorders in his 1973 work An Introduction to Methods in Cognition No.1 Self Musical, all the while standing in a T-shirt inscribed with the words THIS IS ME (“Kore-ha-watashi-dearu” in Japanese). While their methods may differ, artists used recordings to take a critical look at their lives, which had become inseparable from technological developments after the time of the Expo ‘70 in Osaka. Similarly, TAKAHASHI Mizuki discusses the impact of the 2011 East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami on Kamimura’s night passage, after which Kamimura more broadly adopts field recordings in his work.[2]

The roaring sounds of perfect circle strike a different chord, feeling distinct from Kamimura’s previous works. When considered as a midnight seaside spectacle, the viewer may feel a direct connection with the disaster. However, he does not intend to merely construct an illusion. The piece’s main message becomes clear with a full understanding of SOMEWHERE and the artist’s explanation of his work. Sounds of the waves mix with the noise of dragging the microphone, which hints at an artificial environment. Kamimura explains that the work relates the natural, biological, and human transformations that occur with the waxing and waning of the moon. These factors shift the audience’s perception to the transformation of the senses within an artificial environment. According to Kamimura, the recordings is processed so the audience can experience both the natural and artificial feelings from them.

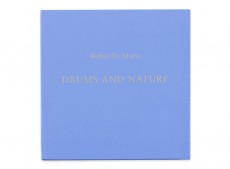

How many people can immediately distinguish the sounds of tides of the new moon from those of a full moon? perfect circle is a petition for the audience to reflect on their own senses, as if urging them to try and recognize the discrepancies. This reflection then connects back to questions about whether we can feel the power that sound and light have over the behavior of living things and the impact they have on our biorhythms. His attempt to sync ourselves with nature’s rhythm through recordings is reminiscent of Walter DE MARIA’s Ocean Music (1968). These questions transcend individual experience and may lead to the exchange of experiences with others. perfect circle can also be compared to Olafur ELIASSON's Weather Project (2003) in that it leads to a dialogue using artificial nature.

R. Murray SCHAFER, a proponent of soundscape theory, states that the wide, layered band of textures in recordings of a seascape stirs the imagination with every listen.[3] In 1969, Irv TEIBEL, a staff member of Tony CONRAD’s film production team, presented an artificial recreation of ocean recordings in Environments 1 after noting the psychological effects of ocean recordings. The genealogy of ocean recordings extends back from Kamimura’s work to Hikosaka and Shibata, and even further, across the ocean, to Teibel and De Maria and earlier.

[1] DAVIES, Hugh, and Caleb KELLY. “Sound and art,” in: Oxford Art Online, updated 16 Oct 2013. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T079882 [Accessed in 26.12.2016]

[2] TAKAHASHI, Mizuki, “The tone of chaos, the sound of an omen,” in: Criterium 82, Contemporary Art Center, Art Tower Mito, 2011.

[3] SCHAFER, R. Murray. The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World, Vermont: Destiny Books, 1994, pp.159-160.

"night passage"

2011,

Photo:SAITOH Tshuyoshi

WADA MORIHIRO

"An Introdaction to Methods in Cognition

NO.1 Self Musical"1973

Photo:unknown

Walter DE MARIA"Ocean Music"

1968,Drums and Nature,

Gagosian,201

Olafur ELIASSON

"Weather Project"

2003,

Photo:Studio Olafur ELIASSON

"Perfect circle"

Mixed media,2016

普遍的な風景

2016年7月30日(土)~9月11日(日)10:00~18:00 会期中無休・入場無料

上村洋一

KAMIMURA Yoichi

《風景画の記憶》

青森の風景画、音、スピーカー、2016年

撮影:山本糾

人工風景を通じて自己を聴く――上村洋一のフィールド・レコーディング作品

金子智太郎

青森の風景を描いた絵画と、それが描かれた場所の音をあわせる《風景画の記憶》、照明が刻々変わる室内に新月と満月の波音を響かせる《perfect circle》、上村の両作品には「フィールド・レコーディング」という手法が使われている。彼は近年、野外で現実音を録音するこの手法を制作の軸にしている。絵画科出身で、並行して音楽も制作していた上村は、最初期の作品から聴覚と視覚の関わりや、音の記録といったテーマに取りくんでいた。映像を楽譜としてあつかう《Conductor of Scenery》シリーズ(2010)や、言語による音の記録であるオノマトペを造形化した《twilight message》シリーズ(2010)、サティの楽曲と楽譜をインスタレーションとして構成した《night passage》(2011)などでは、音の記録のさまざまな形態と造形の組みあわせが試された。ボートで夜の海を漂った記録である《night boat》(2012)以降は、満州に暮らした彼の祖母の記憶と彼自身の日常の音を重ねあわせる《grandmother, prologue》(2015)、梅沢英樹とともに世界中の作家から氷の音の録音を募った《0℃》(2016)と、フィールド・レコーディングが作品の核になってきた。

サウンド・アートの理論家、カレブ・ケリーによれば、フィールド・レコーディングをインスタレーションや映像を組みあわせることは、今世紀以降のサウンド・アートのひとつのトレンドである[1]。彼が代表的作家としてあげたスティーブン・ヴィティエロは、ワールド・トレード・センターの録音で知られる。《World Trade Center Recordings》(1999)はこの建築の91階で制作された。固体の振動を電気信号としてとらえて音に変換するコンタクト・マイクロフォンを用いて、ヴィティエロは建築自体の震えを音にした。地上はるか高みにある録音地点は、気象や付近を通過する航空機の影響を敏感に受けとっていた。彼の《Listening to Donald Judd》(2007)は、テキサス州マルファの野外にあるジャッドの作品に対して同様のアプローチを試みた。

《Listening to Donald Judd》と上村の《風景画の記憶》は、既存の造形作品をテーマとするフィールド・レコーディングという点では共通するが、両者の音はまったく異なる。前者は、環境の影響を受けるミニマルな立体の振動を変換した、静かなうなりのような、抽象的なノイズが中心である。《風景画の記憶》から聞こえる音は、鳥や蝉の声、硫黄ガスが吹きあがる音、有線放送の音といった、具象的な音であり、録音された場所の情景を喚起する。これらの音は風景画のサウンドトラックまたはBGMに聞こえないこともない。

しかし、上村の作品は、絵画と録音の曖昧な結びつきではなく、両者の対比にこそ関心を向けているように見えた。BGM用スピーカーは目立たない場所に置かれるが、《風景画の記憶》のスピーカーやケーブルは雑然と床に置かれ、視覚世界とは別の秩序が存在することを主張している。風景画は個々に額縁の向こう側の世界を見せるが、音はその空間のなかで混ざりあう。ある風景と、まったく別の場所の音が、鑑賞者の経験のなかで組みあわさることもある。こうした眼と耳の違いに導かれて、《風景画の記憶》を構成するさまざまな対比関係が頭に浮かんだ。手による記録と機械による記録。過去と現在。風景画家たちの体験と上村の体験。対比されるものをつないでいるのは場所や風景、その記録や記憶といった観念である。だが、《風景画の記憶》は場所や記録というものを本質的に分裂したものとして表現するのではないか。眼と耳が(また鼻や舌や皮膚が)異なるかたちの記憶をもつなら、個人の記憶がひとつのまとまりとして経験されるのは、偶然にすぎないだろう。上村は《grandmother, prologue》でも、聴覚と視覚の対比と、別の人間の経験の対比を重ねあわせていた。

《風景画の記憶》を通じて、私は経験の成りたちに思いをめぐらせた。この意味で、この作品には70年代の日本でいくつも制作された、録音を通じて感覚の働きを観察しようとする作品との共通性が感じられる。《フロア・イベント》(1970)が注目された彦坂尚嘉は、同時期に《SEA FOR ROOF》(1972)などで柴田雅子と屋根から海の録音を流した。和田守弘は《認識に於ける方法序説 No.1 SELF・MUSICAL》(1973)で複数のレコーダーから異なるメッセージを流し、自らも「コレハワタシデアル」と書いたシャツを着て立った。手法はさまざまだが、彼らは大阪万博の後に、テクノロジーの展開と不可分になった自らの生活を批判的に見つめるために、録音を用いた。高橋瑞木は上村の《night passage》をめぐる文章のなかで、同年の震災が彼の作品にもたらした影響を論じた[2]。上村はこの作品以後、フィールド・レコーディングを大きく取りいれていった。

《perfect circle》の轟音はこれまでの上村の作品と印象を異にする。この作品を夜の海のスペクタクルと考えれば、震災との直接的なつながりも感じられるだろう。しかし、《風景画の記憶》や、彼の作品解説をふまえると、イリュージョンの構築とは別の、この作品の主眼が見えてくる。波音にはマイクを引きずるようなノイズが混ざり、人工環境であることが示唆される。彼の解説に書かれているのは、月の満ち欠けにともなう自然、生物、人間の変性である。これらは《perfect circle》の鑑賞者の意識を、人工環境のなかでの感覚の変性に向かわせようとする。上村によれば、録音は自然な質感と人工的な質感の両方が感じられるように加工してあるという。

満月と新月の海の違いを録音からただちに聞き分けられる人はどれだけいるだろうか。むしろ、この作品はその違いを聞きわけようと試みるように、そして自らの感覚を反省するように鑑賞者をうながす。この反省はさらに、音と光の移りかわりに生物の行動を左右する力を感じられるか、自らのバイオリズムへの影響を感じられるか、といった問いにつながる。録音を介して自然のリズムとの同調をはかる試みは、ウォルター・デ・マリアの《Ocean Music》(1968)を思わせる。また、先の問いは個人の経験にとどまらず、他者との経験の交換にもつながるかもしれない。人工的自然を通じて対話を導くという点で、この作品はオラファー・エリアソンの《Weather Project》(2003)とも比較できるだろう。

サウンドスケープ理論の提唱者マリー・シェーファーは、海の録音には広帯域のテクスチャーが含まれ、聴くたびに新しいイマジネーションをかきたてると語った[3]。トニー・コンラッドの映画制作スタッフだったアーブ・タイベルは、波音の録音がもたらす心理的効果に注目し、1969年に人工波音のレコード「Environments 1」を発表した。デ・マリア、タイベル、彦坂と柴田、上村の作品の前にはこうした海の録音の系譜がある。

[1] Hugh DAVIES and Caleb KELLY “Sound and art”, in: Oxford Art Online, updated 16 Oct 2013. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T079882 [Accessed in 26.12.2016]

[2] 高橋瑞木「混沌の音色、予兆の響き」、『クリテリオム82』、水戸芸術館、2011年。

[3] R. Murray SCHAFER The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World, Vermont: Destiny Books, 1994, pp.159-160.(R. マリー・シェーファー『世界の調律――サウンドスケープとはなにか』鳥越けい子、小川博司、庄野泰子、田中直子、若尾裕訳、平凡社、2006年、325-326頁。)

《night passage》

2011年

撮影:SAITOH tsuyoshi

和田守弘《認識に於ける方法序説

No.1 SELF_MUSICAL》

1973年、撮影者不明

ウォルター・デ・マリア

《Ocean Music》

1986年

(CD「Drums and Nature」2016年》

オラファー・エリアソン

《Weather Project》

2003年

(撮影:Studio Olafur ELIASSON》

《パーフェクト・サークル》

ミクストメディア、2016年