passage 永遠の一日

2015年7月25日(土)~9月13日(日)10:00-18:00/会期中無休・入場無料

風間サチコ

KAZAMA Sachiko

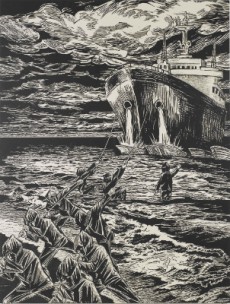

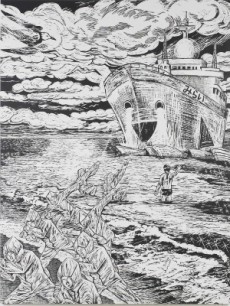

《帰り船(黒い座礁)》《帰り船(白い未来)》

木版画(和紙、油性インク、パネル)、242×183cm(2点組)

撮影:山本糾

版表現における主題と構造の符合と脱構築、そしてその超越

服部浩之

風間サチコは、彼女自身が生きる現在という時間と空間を起点とし、政治的、社会的な出来事を主なモチーフに選び、その出来事や社会に対する彼女の疑問や憤りをブラックなユーモアとともに織り込み、墨一色の木版画を完成させる。風間自身はビアズリー[i]やジャポニズムの影響を受けたと述べている[ii]が、日本の漫画を想起させるようなキャラクターや描線をも見出すことができる。その表現には、白々しい明るさとともに、戦後日本が歩んできた高度経済成長の裏側で勃発した出来事や黒い歴史を扱うことが多いためか、不穏な暗雲立ち込める気配も同時に存在するのだ。

具体的な歴史的事象に基づいて組み立てられるコンセプトと作品構造はとても明解だが、緻密な構成により絵画的に構築された世界は、単純な合理性とは一線を画し、むしろ合理性や効率性を優先してきた社会が孕む矛盾のようなものに対する疑義が、ことばでは説明できない多様で魅惑的な描線に託されているようにも感じられる。また、風間は木版画という本来複製可能なメディアを選択するが、その作品は常に一点を刷るのみで複製されることはない。

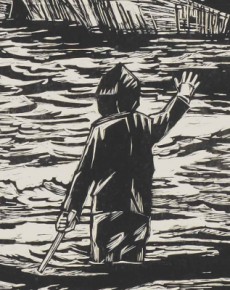

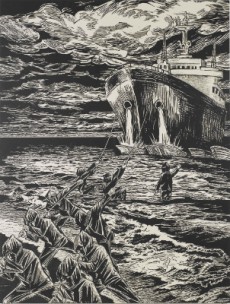

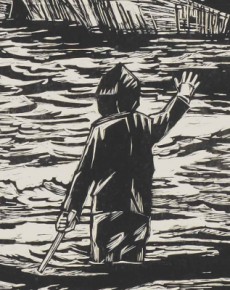

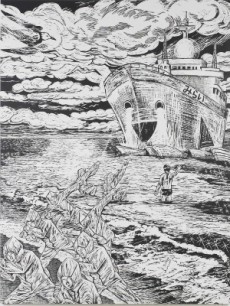

一方で、本滞在制作では「彫る」という木版画の特性を最大限に拡張し、同時に版画であるにもかかわらず絶対的に複製不可能な独自の版表現の在り方を見出し、《帰り船(黒い座礁)》、《帰り船(白いみらい)》という二点の対となる作品を制作した。構図がほぼ同一のため、一見すると白黒反転したのみとも見えてしまうこの二つの作品は、《帰り船(黒い座礁)》の版を、さらに彫り進めることで《帰り船(白いみらい)》を生み出したという関係にあり、この二点は時間の流れとしても一本の線状にあるのだ。二作品に描かれている主要モチーフは、その姿と役割を大きく変えられた一隻の船である。原子炉を動力源とする「原子力船むつ」は、戦後の原子力の平和利用という政策のもと1968年に着工された。「むつ」は1974年に太平洋上で初の原子力航行試験が行われている最中に放射線漏れを起こし、母港となるはずであった陸奥大湊港への帰港を住民らの反対で拒否され、その後16年にわたって日本各地の港を彷徨いながら改修を受け、四回の試験航行後に原子炉を撤去され、ディーゼル機関に積み替えられ「海洋地球研究船みらい」へと姿を変えたのだ。つまり、《帰り船(黒い座礁)》は「原子力船むつ」を、それを彫り進めて生まれた《帰り船(白いみらい)》は「海洋地球研究船みらい」をモチーフとして、高度経済成長のもと楽天的に進められた原子力政策のほころびを象徴するような存在となってしまった一隻の船の劇的な変化を、同一の版を「彫り進める」という手法で構造的も見事に表現しているのだ。日本社会の表と裏、明と暗を表象するような数奇な運命を辿ったこの船を、雨合羽に覆われた無表情の人が陸へと引っ張っていく様子を重々しくもコミカルに描き出すところに、表面のみを繕い不都合を覆い隠してしまう現代社会への風間なりのアイロニー交じりの憤りのようなものが現わされているだろう。また、人が船を曳く様子は、このような事件は結局人が生み出したもので、やはり人間が後始末をするしかない、ということも思わせる。すると、「みらい」を曳く人々の白い雨合羽は福島第一原子力発電所の作業員たちの白い防護服を彷彿とさせるだろう。ちなみにこの「みらい」は、2011年3月末に福島第一原発事故の海洋汚染を調べるため、福島県沖に派遣され海水を採取したという。なんと皮肉な運命だろうか。

ところで風間は、「passage 永遠の一日」という本展のテーマを独自に咀嚼し、青森の地における滞在制作という条件を引き受け、見事にひとつの新作に結実させた。「原子力船むつ」という忘れられた存在を召喚することで、青森が抱える原発などの諸問題について再考することを促し、我々の想像を超える永遠とも感じられる長い半減期をもつ放射性物質の存在や、先が見えない原発の廃炉作業のような何世代にもわたって引き継がなければならない課題なども想起させる。また、原子力船から地球観測船への転換の旅をひとつの航路(=passage)と捉え、その時間の推移(=passage)を版の変化において表現しているのだ。通常「みらい」ということばは将来への肯定的な印象を与えるものだが、船体に刻まれた幼稚な描線による「みらい」という文字からは、幸福な未来を想像するのは容易ではなく、むしろ先行き不透明で不安な将来が思い描かれてしまう。

現実の出来事を基底としながらも、それを脱構築し少々ブラックな表現へと昇華するあたりには、ナンセンス文学[iii]なども想起されるだろう。現実世界で引き起こる諸問題を主題として扱いつつも単にその問題や状況の批判に終始するのではなく、芸術という創造と表現の行為を介してのみ成立しうるフィクショナルな飛躍を挿入する風間の態度には、より普遍的で長期的な視野での鑑賞や批評に対峙する超越的な存在としての作品を残そうという意思を強く感じるのだ。風間は、「概念にとらわれない純粋な表現としてこれから先耐えられるようなものをつくりたい」[iv]と述べている。本作においては、初見では描かれている対象やその背景、あるいは二つの作品の関係や構造に注視しがちだが、しかし最終的には強い線が彫られていることや絵画的で精密な構成など、結局版画としての純粋な強度に目を奪われ、作品の前に立ちつくしてしまう、まさに永遠の一日という瞬間が経験されるのだ。

Passage: A Day in Eternity

10:00am-6:00pm, July 25 - September 13, 2015/ admission free

KAZAMA Sachiko

風間サチコ

"Homebound Ship (Beached Black)"

"Homebound Ship (Future White)"

Permanent pen and paint on the wall, chairs and sound piece created with the collaboration of Paula NISHIJIMA

photo: YAMAMOTO Tadasu

Compatibility and deconstruction between the subject and the structure in print expression, and their transcendence

HATTORI Hiroyuki

Choosing political and social events as her main motifs while starting from her standpoint in the present time and space, KAZAMA Sachiko completes her woodblock prints all in black ink, incorporating her doubts and anger about society and related incidents with black humor. She says that she has been influenced by Beardsley[i] and Japonism[ii] while we find characters and lines seen in Japanese manga in her works. There is a sign of dark disturbing clouds together with feigned brightness in her expressions, probably because she takes up events and dark history behind the rapid economic growth in Japan after World War II.

While the concept and work structure constructed on the basis of specific historical events are well defined, the world that has been constructed pictorially through elaborate composition demarcates simple rationality. Rather, doubts about contradictions conceived by the society giving priority to rationality and efficiency seem to be included in diverse and fascinating lines that are difficult to explain with words. Additionally, despite the fact that she chooses woodblock printing that is primarily a replicable medium, she prints only one original and does not make editions.

On the other hand, for this residence program, she produced a pair of prints; Homebound Ship (Beached Black) and Homebound Ship (Future White), maximizing the characteristic of woodblock prints, that is “carving,” to find her original way of printing representations that is absolutely non-replicable disregarding they are prints. As these two pieces have similar compositions, it seems at first glance that white and black are merely inverted. However, Homebound Ship (Future White) was produced as a development of Homebound Ship (Beached Black). Therefore, these two pieces are on the single line in the flow of time. The main motif depicted in them is a ship whose appearance and role have been greatly changed. The construction of Nuclear Ship Mutsu with a reactor as its power started under the policy of peaceful use of the post-war nuclear power in 1968. Mutsu caused a radiation leak while the first nuclear power navigation test was being carried out in the Pacific Ocean in 1974. As local residents refused to have Mutsu return to Mutsu Ohminato Port, which had been supposed to be its home port, it received repairs while hanging around harbors throughout Japan over the next 16 years, had the reactor removed after four trial navigations, and the power was changed to a diesel engine. Finally it was transformed to Oceanographic Research Vessel Mirai. In other words, the motif of Homebound Ship (Beached Black) Homebound Ship (Beached Black) is Nuclear Ship Mutsu, and Oceanographic Research Vessel Mirai is for Homebound Ship (Future White). This dramatic change of a ship symbolizes a flaw in the nuclear policy pursued optimistically during the period of high economic growth, and it is excellently expressed structurally by a technique of “carving onward” on the same woodcut. This ship with a checkered history as if to represent two sides—light and dark—of Japanese society is pulled by stone-faced men wearing raincoats. In this serious but yet comical depiction, it seems that Kazama’s anger mixed with irony towards today’s society, which patches things up and conceals inconveniences is expressed. What’s more, the way in which people are pulling the ship tells us that such incidents are caused by humans and so they should deal with the aftermath after all. White raincoats worn by people pulling Mirai remind us of white protective clothing worn by people working at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. Incidentally, this Mirai was sent off Fukushima at the end of March 2011 to collect seawater in order to examine radiation contamination by the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident. It is truly an ironic fate.

Having assimilated the theme of this exhibition “Passage: A Day in Eternity” from her independent standpoint and taken on the condition of the residence program in Aomori, Kazama has achieved a wonderful result in her new work. By recalling Nuclear Ship Mutsu, a forgotten existence, the artist encourages us to rethink issues such as a nuclear power plant in Aomori. Also she reminds us of the presence of a radioactive substance with a long half-life, which seems like eternity, as well as challenges to be passed on to many generations such as shutting down a nuclear reactor in an unpredictable future. Additionally, regarding the journey of conversion from a nuclear ship to an oceanographic research vessel as a passage, she shows the passage of time through changes on the woodcut. Generally speaking, the word mirai (future) gives a positive impression of the future, but it is difficult to imagine a happy future from the word “Mirai” engraved in childish writing on the hull. Rather, uncertainty and anxiety in the future are envisioned.

While based on real events, the artist deconstructs and sublimates them into satirical representation, which reminds us of nonsense literature.[iii] While handling problems taking place in the real world as subjects, she is not always simply criticizing problems and situations, but takes a fictional leap, which is possible only through acts of creation and expression of art. There, we feel strongly her intention to leave artworks as transcendental existence facing art appreciation and critique in a more universal and long-term perspective. Kazama says, “I’d like to make long-surviving works as a pure form of expression free from concept.”[iv] Seeing these works for the first time, we tend to watch depicted objects, their backgrounds, or the relationship between the two and their structures. Eventually, however, we are fascinated by the pure strength of the prints including strong carved lines and pictorial, precise compositions, standing overwhelmed in front of the work. That very moment feels like a day in eternity.

[i] Aubrey Vincent BEARDSLEY (1872—1898)

[ii] Interview with KAZAMA Sachiko, AC2, 17 (Aomori: Aomori Contemporary Art Centre, 2016).

[iii] A kind of literature that combines things with and without meanings, ignores commonplace rules and logicality in using words, and tries to destroy them.

[iv] Kazama, AC2, 17.