Material & Mechanism

October 25 ~December 14, 2014.

LIAO Jiekai

リャオ・チエカイ

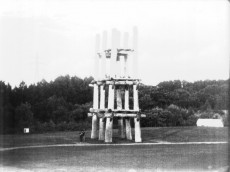

LIAO Jiekai "Something from the ocean and something from the hills"

photo: YAMAMOTO Tadasu

Tactile Light

KONDO Yuki

Uncovering people’s memories and hidden regional history, LIAO Jiekai makes films and installations using films to poetically evoke the relationship between what we see and what we remember. He often uses 16-mm film in his work, and in addition to using its peculiar texture effectively, he focuses on the materiality and mechanism of film. As the title, which the artist quoted from a novel, indicates(1), Something from the ocean and something from the hills produced this time is a film, and he got the idea from the local topographical features. At the same time, in concert with our residence program theme, “Material and Mechanism,” the materiality of the 16-mm film and the mechanism of a projector are used as a metaphor in this installation.

To produce this work, Liao went to the city of Aomori almost every day during a certain project period in order to shoot for several minutes the so-called “magic hours” to gain a view of sunset late in autumn, which changed every day. To decide on where to film, he first got a rough idea on a map in advance, checked locations by Google Street View, and chose shooting sites which he thought were visually interesting and/or reflecting the regional characteristics. In doing this, he divided the city map of Aomori into several zones so that he could film every day moving from the seaside towards the hills following each zone to end at the exhibition venue ACAC on the last day.

Although the film was taken according to the rules arranged by the artist concerning the schedule/length of time and the site selection, the moving images are full of emotions, reflecting powerfully the artist’s experiential impressions and sensations: the impression of a beautiful sunset he saw during his stay, a landscape of the city extending towards the sea which he saw at the airport on the hill on arriving in Aomori for the first time, and the light changing from moment to moment in seasons from late summer to autumn and winter. A small monitor set up at the exhibition venue shows an animated version of the map of Liao’s shooting locations as if to follow his path, adding his physical experience to the work.

The images are not only visually interesting but also grasp a local aspect of the region, which has existed along with accumulated time, when someone views it metaphorically from another angle being aware of the horizontal axis representing a present-day context and the vertical axis a historical context. The landscape that has changed over the years and the landscape that has not changed such as remains and graveyards belonging to the past, contemporary buildings against the backdrop of a mountain range, a stream-flow and a path made by people, are folded in ambiguous time between the daytime and nighttime. Probably, the landscape where “something from the ocean and something from the hills” are mingled used to be deeply involved with the local mentality in the first place. Stone circle ruins from the Jomon period, that are said to have been ritual sites, still remain where we can have a panoramic view of both a mountain range of Hakkoda towering over in the background and the Bay of Mutsu, which tells us that it used to be a special landscape for ancient people. And in this same topography, people from different timeframe lived while leaving various traces. Such scenes can be clearly found in ordinary objects and people’s ordinary daily life, as if these subtle accumulations were concealing the history of landscape. Those scenes were recorded on Liao’s 1000 foot-long film, and it runs about 28 minutes.

It is not because the images are lyrical that we find them impressive and sensuous. As they are filmed on black-and-white film, beauty of colors peculiar to the light after sunset is not captured, so what his camera captured in the magic hour is not the so-called dramatic “pretty scene” during that specific timeframe but, you might say, it is ambiguous, subtle light itself. This feeling is also relevant among the landscape with water such as a river or pond he often focuses in the film. According to the artist, he shoots a landscape with water because he is interested in water as something connecting mountains and the ocean. On the other hand, however, the main focus is on light itself surrounding the artist, as the Impressionist painters often painted water trying to capture light. What is the main focus is made clearer in its relation to the installation.

The filmed images were projected from a projector inside the gallery onto the screen set up outdoors. In strong daylight, therefore, it is difficult to discern images projected from the projector onto the screen. Instead, the visitors see the captured image through a singular strip of a 1000 foot-long film displayed in the gallery. It shows the material quantity of 28-minute long film emerging in the light. Here, the materiality of the printed film itself is more conspicuous than the projected images. Both a long strip of film which shows a series of continuous images and projected images that are invisible on the screen reveal the animation mechanism, which gives us an illusion that photographs shown continuously at the speed of 24 frames per second appear to be moving, and also reveal a mechanism of optical instrument for screening.

As it gets dark and the film as a material begins to hide its existence in the darkness, the moving images, which do not exist physically, begin to make its presence strongly felt on the contrary. The moving images strongly discernible in the darkness are reflected intricately on water, glass and walls, heaping up its layers of truth and untruth. A window frame casts a shadow unexpectedly on the screen, not only lays real and virtual images on top of the other, but also makes us feel as if the scenes on the screen were what we are actually looking at through an open window as depicted in a painting. That evokes us to think of the relation between reality and illusion. With a texture of coarse particles peculiar to celluloid film and the scenes filled with vague light after sunset, the film increasingly shows vague and magical landscape. It is even more so as the shooting location moves towards a mountain and naturally formed shapes turn abstract, and it gets dimmer as the sun sets.

The installation of film, in which light changes its expression through light, refers to the mechanism of moving images, and at the same time, indicates its materiality. Visual illusion, whose connection with the body is severed, comes down to us from its absolute position when tactile perception is added by several means. It not only indicates the limit of images but also reminds us of uncertainty and impermanence of everything.

(1)KUROYANAGI Tetsuko, Madogiwa no Totto-chan (The Little Girl at the Window), Kodan-sha, 1981.

Translated by NISHIZAWA Miki