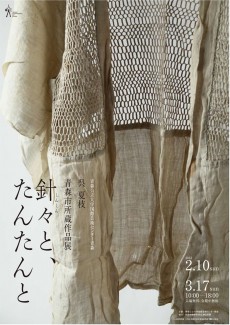

OH Haji × Aomori City Archives Exhibition “Gestures in Clothing”

Having learned the art of dyeing and utilizing techniques such as weaving, dyeing, tying, and stitching in her pieces, artist OH Haji sheds light on the untold history and stories of women and unnamed individuals through her art. Through artists such as OH, this exhibition aims to present the works of the former Keiko Kan Museum, now part of the folk materials and collections archived by the Aomori City Board of Education, from another perspective. The Aomori Contemporary Art Centre (ACAC) will exhibit traditional Kogin-zashi and Hishi-zashiworks made primarily of hemp fabric, which give us a glimpse into the histories of the individuals who owned and wore them: work clothing, undergarments, and mosquito nets among other commonplace objects. OH Haji’s past works and newest photography will also be on display. It is said that clothing is one’s second skin. In this exhibition, the ACAC attempts to depict the rich lives of the unnamed people hidden in the threads of these clothes and fabrics by displaying items in a way which allows the viewer to feel the body warmth and memories stitched within them.

* The Keiko Kan Folk Heritage Museum of Aomori City

Opened in 1977 as the Keiko Kan Foundation and transferred to the municipal government of Aomori City in 1998, the Keiko Kan Museum was a folk heritage museum. It was closed in 2006. Its collections contained and displayed regional folkcrafts such as Kogin-zashi and Hishi-zashi embroidery, Funadansu chests and baskets, and excellent Ainu folk materials which tell the history of interaction and trade with Hokkaido Ainu. After its closure, the archives were transferred to the Aomori City Board of Education.

———

Exhibition view

Mosquito net

OH Haji, Sange, 2005

OH Haji, Flower spot, 2007

Photo; YAMAMOTO Tadasu

————————————————-

Their needles and looms constant as the winter snows

OH Haji

August 17, the fifth day of investigation in the archives. Arriving at the archives around half past ten, I greet the staff and climb the stairs to the second floor. As always, I begin my preparations by placing my research materials on the desk and spreading out a cloth on the floor. On it I place my camera and gloves. Today I plan to inspect mosquito nets and undergarments. I find a mosquito net hidden within a box high on a shelf in the archives, so I have the staff help me lower it down. Just under the box’s lid lies a letter penned in dark ink on Japanese paper:

Made by YOSHIKAWA Hisa 15 years old at the time

1869 – Born February 8, 1963 – Died at the age of 94

1877 – Planted a hemp seed.

She took the hemp and wove it into a mosquito net, which she took with her as part of her bridal trousseau. Originally it also had metal fittings, but they were collected with other precious metals during the war and are no longer attached.

-KITABATAKE Mitsu (Grandchild)

The archives where I spent eight days researching in August 2012 holds regional folkcrafts that were once stored at the Keiko Kan Folk Heritage Museum of Aomori City. Everyday items and clothes, mainly traditional kogin-zashi and hishi-zashi embroidery, are placed in one of its rooms. The boxes are neatly aligned on big shelves. Fabric materials like kimonos are packaged a few to a box, each delicately wrapped in protective Japanese paper. For my current research, I only came to the archives after exploring its collection through its database and browsing materials from previous exhibitions at the Keiko Kan Folk Heritage Museum of Aomori City.

I had intended to begin inspecting items that I had set my sights on beforehand. In the process, other items sharing the same box began to intrigue me, so I ended up emptying each box to study each of its contents. One by one, I would untie the knot of the protective paper wrapping, spread the garment out on the cloth, snap some photographs, and jot down some memos. In this repetitive rhythm, I was able to see around 30 pieces on the first day. At first, I had planned to have a look at all of the daily goods and handiworks connected to fabric–kogin, hishi-zashi, sakuri, and sashiko-stitched donja (nightwear)–within five days, but there were so many materials just looking at kogin that I had to narrow my research down to kogin and hishi-zashi alone. Until then, I had always thought of kogin as white patterns stitched onto indigo fabric; however, I also learned of the variances in kogin patterns depending on region and the existence of other kogin called “niju-sashi kogin” (double-stitched kogin) and “somekogin” (dyed kogin). What especially caught my eye on the first day of my investigation was the texture of the fabric, which would have been impossible to discern by only searching the database.

Kogin was originally written in different Chinese characters, all of which refer to an unlined, hemp kimono used as work clothing.(1) The needlework needed to reinforce and insulate the clothing gradually produced unique patterns and became what we now know as “kogin”. Kogin made in the Tsugaru region was primarily made in three areas, which are divided into “East Kogin,” “West Kogin,,” and “Mishima Kogin” (Three-striped Kogin). Moreover, though kogin in the Tsugaru region was stitched into kimonos, these same patterns were stitched into aprons and leggings and called “hishi-zashi” in the Nanbu region. Aomori’s cold climate is ill-suited for cotton cultivation, and farmers’ livelihoods were restricted by the thrift ordinances of the feudal period.(2) Under these strict thrift ordinances, farmers were prohibited from wearing heat-retaining cotton and therefore limited to wearing hemp cloth. Kogin patterns were originally woven with hemp thread, but as cotton thread became more available, white cotton thread was stitched onto indigo-dyed hemp fabrics.

In my research this time, it wasn’t only the beautiful white on indigo kogin, but also the niju-sashi kogin (double-stitched kogin) and somekogin (dyed kogin) that were new discoveries for me. Niju-sashi kogin refers to patchwork over holes and threadbare areas in kogin kimonos. The heavy, overlapping cotton yarn covers a gap in the pattern like a scab over a scrape.

Bast fiber made in Aomori was mostly made from hemp, with small amounts made from ramie.(3) Hemp can be harvested annually and gives high yields. In comparison, ramie is a perennial plant with small yields and is difficult to cultivate, so it seems that it was valued as a fine-quality material.(4) As mentioned in the previous paragraphs, hemp was grown for private use to make clothing, sacks, futon covers, and mosquito nets in addition to other items.(5) Freshly spun hemp thread was very rough, so it was boiled in lye, exposed to the sun, and soaked in cold water repeatedly. Sun-bleached hemp and ramie cloth was either dyed with homegrown dyer’s knotweed (tadeai) or dyed indigo at a professional dyers. After dyeing, fabric was then softened again by beating it with a wooden mallet.

Somekogin were kogin kimonos that were re-dyed indigo after the dark blue cloth and white patterns had become tarnished. It appears to have been worn particularly among the elderly.(6) Kogin is said to have been passed down and worn across generations.(7) When looking at somekogin, we can see just how much one kogin was cherished; kogin that began as someone’s Sunday best turned into everyday clothing and finally to work clothing, unraveled and re-stitched many times in the process. A unique softness also appears from beating after washing and dyeing. Gestures in the clothing remain vivid as evidence of their owner’s years of hard work. Somekogin made of ramie have gained a black luster and flexible texture.

The dirty and frayed remnants, patchwork of niju-sashi kogin, and deep blue hue of somekogin are the evidence of daily labor, and we can also say that they are the evidence of someone’s life. Naturally, these traces are not made intentionally, but they possess a value incomparable with anything else. The patterns in kogin and hishizashi are created through counted stitch embroidery. Kogin patterns are made from odd numbers of stitches on the weft while hishizashi patterns are made from even numbers of stitches. In kogin, there are a few dozen types of plant and animal patterns like beko-sashi (cow stitch) and mameko (little bean), which are repeated as the basic theme and surrounded by vertical, horizontal, and diagonal straight lines to create the overall pattern. At around five or six, farmer’s daughters were taught the basics from their grandmothers, mothers, and older sisters to begin stitching small items with needle and thread. These girls are said to have been able to stitch patterns by around ten years old. They would begin stitching kimonos and mosquito nets at 14 and would stitch four or five of by the time of marriage as a bridal trousseau. It seems that skilled women were able to stitch various types of patterns, but certain patterns were only stitched in certain regions, so it is said that regional characteristics manifested themselves in their patterns. Dissemination of a pattern is said to have occurred when a woman of a certain village married into a family of another village.(8)

The immense task of producing clothing, which began with planting the seed, was the accumulation of tremendous toil, but there must have been joy and amusement in the creation and inheritance of various patterns over generations. Indeed, vivid scenes are recorded where friends and peers would get together to vie with each other for the best stitch.(9) Within the various kogin patterns, there is one called “kutsuwa-tsunagi.” This pattern acted as a talisman against evil(10) and could be thought of as a manifestation of an everyday prayer. In this way, I believe that prayers must have been woven together with the solid touch of the thread. Time spent stitching fabric amidst silent winter snows was invaluable, unencumbered, and entirely that of the woman stitching. There were women who went about their common daily routines treasuring this alone time.

I displayed works created in 2004, 2005, and 2007 in this year’s exhibition. Behind my choice of the textile-dyeing technique is the influence of my mother. I would often copy my mother’s sewing by making clothes for my dolls. Seeing that I had chosen textile-dyeing as my major in college, my mother kept my grandmother’s chima jeogori and hemp cloth for me.

In my 2004 work Three Generations of Time (Mittsu no Jikan), I transferred three pictures–one of my grandmother, one of my mother, and one of me, each in a chima jeogori–onto my grandmother’s hemp cloth fabric. It symbolizes living in different times which overlap in a memory of the everyday. Clothing as a second skin is the motif in my works Sange (2005) and Flower Spot (2007). I began Sange by weaving fabric and eventually tailored clothing out of the fabric. That clothing is the assured proof of my existence.

The vestiges left in clothing tell the story of an individual. There are people who have kept others’ stories alive and safe by writing their histories and backgrounds, carefully folding and storing each piece of clothing. At the beginning of this essay, I introduced a letter from KITABATAKE Mitsu-san. Her words embody this sentiment perfectly; through her words, we begin to see the story of an individual through her clothing. The moment that I saw a connection in the distance with my own work is when this exhibition came into view. I heard the sounds of needles and looms constant as the winter snows.

(1)『刺し子の世界―受け継がれた技―』、青森市歴史民俗展示館稽古館、2005年、5頁。(The World of Sashiko Needlework — Technique passed down through the generations, Keiko Kan Folk Heritage Museum of Aomori City, 2005, p. 5. ) (catalogue)

(2)『装う―生活着にみる先人の知恵と技・こぎん刺しと菱刺しの世界』、青森市歴史民俗展示館稽古館、1999年、7頁。(Appearance: The World of Kogin and Hishizashi/Techniques and wisdom of our predecessors through everyday clothing, Keiko Kan Folk Heritage Museum of Aomori City, 1999, p.7. ) (catalogue).

(3)飯田 美苗「麻糸のできるまで」、『季刊稽古館』、vol.15 、財団法人稽古館友の会、1995年、11頁。(IIDA Minae, “The Making of Hemp Thread” in Keio Kan Quarterly vol. 15 , Friends of the Keiko Kan Foundation, 1995, p.11.)

(4)横島直道編著『津軽こぎん』、日本放送出版協会、1974年、23頁。(YOKOZIMA Naomichi, Tsugaru Kogin, NHK Publishing, 1974, p.23.)

(5)『津軽こぎん』、149頁。『装う』、9,12頁。(Tsugaru Kogin, p.149, Appearance, p.9, p.12.)

(6)『刺し子の世界』、28頁。(The World of Sashiko, p.28.)

(7)『装う』、12頁。(Appearance, p.12.)

(8)『津軽こぎん』、79-81頁。(Tsugaru Kogin, p.79-81.)

(9)『津軽こぎん』、149頁。(Tsugaru Kogin, p.149.)

(10)『刺し子の世界』、12頁。(The World of Sashiko, p.12.)

—————

|Biography|

OH Haji

Born in Osaka Prefecture in 1976. She is now lives and works in Osaka after completing her Ph.D. in Fine Arts at the Kyoto City University of Arts. She primarily creates works utilizing the techniques of weaving, dyeing, embroidering, knitting, and tying. She does not interpret clothing to be mere symbols, but to be one’s second skin. In recent years, she interprets textiles and knitted fabrics as metaphors of the time and memories woven within them. By unraveling their threads, she produces works which expose things left lost in the threads and unexpressed in words. In addition to her invitations to exhibitions such as the “Young Artist Selective Exhibition” (The Museum of Kyoto, Kyoto, 2007) and “Inner Voice Uchinaru Koe” (21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, Ishikawa, 2011), OH Haji performs numerous textile-related workshops.

Organized by: Aomori Contemporary Art Centre (ACAC), Aomori Public College

In Cooperation with: Aomori City Board of Education and the Aomori City Board of Education’s Cultural Properties Section

>>Press Release こちら

- Date

- Feb 10 (Sun) - Mar 17 (Sun). 2013

10:00-18:00

ちょま夏用肌着(青森市教育委員会所蔵)撮影:呉夏枝